All Right Now

3 Febbraio 2025

Giani convoca i comitati amiatini

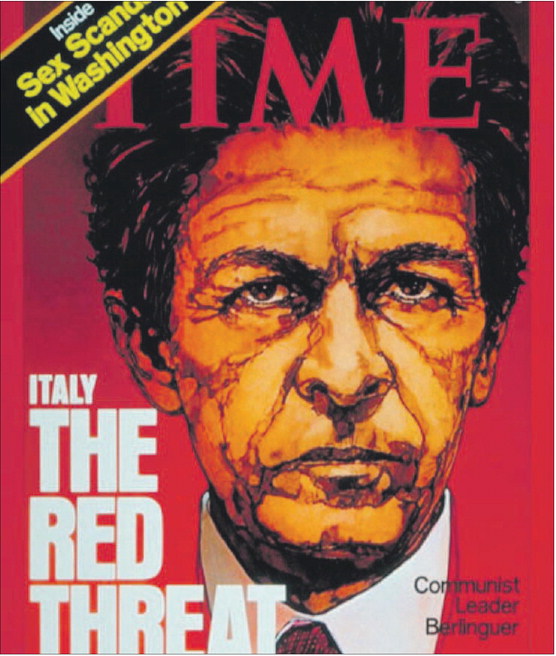

3 Febbraio 2025Giorgia Meloni ha grandi ambizioni bancarie

Il primo ministro nazionalista italiano riuscirà a concentrare il potere finanziario?

Ci sono vari modi di guardare all’inaspettata offerta da 13,3 miliardi di euro (13,9 miliardi di dollari) che Monte dei Paschi di Siena (MPS) ha fatto per Mediobanca il 24 gennaio. A prima vista, testimonia una notevole ripresa da parte di MPS, la banca più antica del mondo, che è stata salvata dallo Stato italiano nel 2017 a un costo di 5,4 miliardi di euro. E se il tentativo di acquisto da parte di MPS della banca d’investimento fondamentale italiana venisse accettato, l’accordo porterebbe a un gradito consolidamento nel frammentato settore bancario italiano. Ma c’è anche un altro modo di guardare all’offerta. In un paese in cui politica e denaro si sovrappongono in misura insolita, è forse il più utile. Considera cosa significherebbe l’accordo per Giorgia Meloni, primo ministro italiano.

In breve, potrebbe estendere l’influenza della sua coalizione di destra non su una, ma su due delle più importanti istituzioni finanziarie italiane. L’offerta di MPS è il secondo tentativo del governo di creare un rivale per i “due grandi” del sistema bancario italiano: Intesa Sanpaolo e UniCredit. A novembre i ministri hanno preparato il terreno per un’unione tra MPS e Banco BPM, un altro istituto di credito commerciale, che è stata interrotta quando UniCredit ha fatto la sua offerta per Banco BPM. Per rispettare le norme dell’UE, lo Stato italiano ha perso la maggior parte del suo interesse in MPS dopo il salvataggio. Tuttavia, rimane il maggiore azionista con quasi il 12% del capitale totale. Inoltre, parte di ciò che ha scaricato è stato acquistato da due investitori che sono stati ripetutamente dalla sua parte nelle battaglie in sala riunioni: Francesco Milleri, che gestisce Delfin, un fondo di investimento per la famiglia di Leonardo Del Vecchio, un defunto magnate dell’occhialeria; e Francesco Gaetano Caltagirone, un magnate ottuagenario dell’edilizia e dei media che è considerato vicino alla Sig.ra Meloni, una connazionale romana. Entrambi hanno anche delle quote in Mediobanca, con Delfin come maggiore azionista della banca. Né il Sig. Caltagirone né il Sig. Milleri sono fan di Alberto Nagel, il capo della banca.

Gli analisti di Barclays, una banca britannica, stimano che, se l’offerta avesse successo, il Tesoro e gli alleati del governo possederebbero più del 26% della nuova entità, abbastanza per il controllo. Ma avrà successo? Agli investitori di Mediobanca vengono offerte 23 nuove azioni MPS per ogni dieci che detengono nella banca target. Anche prima di un calo del prezzo delle azioni MPS in seguito alla divulgazione della sua offerta, ciò rappresentava un premio frugale del 5%. Mediobanca calcola che entro il 27 gennaio era diventato uno sconto del 3%.

In una nota di sfida, i direttori della banca target hanno respinto l’offerta come “fortemente distruttiva di valore”. MPS sostiene che l’assorbimento di Mediobanca libererebbe 700 milioni di euro all’anno di risparmi, rappresentando ciò che Luigi Lovaglio, amministratore delegato di MPS, descrive come “un’incredibile opportunità strategica”. Gli analisti non sono convinti. Temono che eventuali guadagni potrebbero essere compensati dallo scontro culturale che deriverebbe dalla fusione di una banca d’investimento con un prestatore al dettaglio.

Alcuni hanno anche chiesto se il vero scopo dell’operazione sia l’influenza su Generali, la più grande compagnia assicurativa italiana, in cui Mediobanca è il maggiore investitore. Anche lì, Delfin e il signor Caltagirone hanno già quote considerevoli e sono ancora una volta uniti nel criticare il management. Il governo è un altro critico: si è opposto al piano di Generali di unire le forze con Natixis, una società di gestione degli investimenti francese, temendo che potrebbe portare i risparmi italiani ad essere allocati da finanziatori stranieri.

Un’acquisizione di Mediobanca da parte di MPS estenderebbe quindi una matassa di partecipazioni incrociate che sta iniziando ad assomigliare a una che in passato concentrava il potere in una piccola cerchia di potenti mediatori con sede a Milano. È stata annullata da Mario Monti nel 2012. Il signor Monti, che è durato solo due anni come primo ministro, credeva nel libero mercato. Al contrario, la signora Meloni è la leader di un partito nazionalista con istinti protezionistici. ■

Giorgia Meloni has grand banking ambitions

Will Italy’s nationalist prime minister manage to concentrate financial power?

There are various ways to look at the unexpected €13.3bn ($13.9bn) bid that Monte dei Paschi di Siena (MPS) made for Mediobanca on January 24th. At first glance, it testifies to a remarkable recovery by MPS, the world’s oldest bank, which was bailed out by the Italian state in 2017 at a cost of €5.4bn. And if MPS’s attempted purchase of Italy’s pivotal investment bank is accepted, the deal would lead to welcome consolidation in Italy’s fragmented banking industry. But there is also another way to look at the bid. In a country where politics and money overlap to an unusual degree, it is perhaps the most useful. Consider what the deal would mean for Giorgia Meloni, Italy’s prime minister.

In short, it might extend the influence of her right-wing coalition over not one but two of Italy’s most important financial institutions. MPS’s offer is the government’s second attempt to create a rival to the “big two” of Italian banking: Intesa Sanpaolo and UniCredit. In November ministers prepared the ground for a union between MPS and Banco BPM, another commercial lender, which was derailed when UniCredit made its own offer for Banco BPM.

To comply with EU rules, the Italian state has shed most of its interest in MPS since the bail-out. Yet it remains the biggest shareholder with almost 12% of the total equity. Moreover, part of what it offloaded has been bought by two investors who have repeatedly been on its side in boardroom battles: Francesco Milleri, who manages Delfin, an investment fund for the family of Leonardo Del Vecchio, a late eyewear magnate; and Francesco Gaetano Caltagirone, an octogenarian building and media tycoon who is seen as close to Ms Meloni, a fellow Roman. Both also have stakes in Mediobanca, with Delfin the bank’s largest shareholder. Neither Mr Caltagirone nor Mr Milleri is a fan of Alberto Nagel, the bank’s boss.

Analysts at Barclays, a British bank, estimate that, if the bid succeeds, the treasury and the government’s allies would own more than 26% of the new entity—quite enough for control. But will it succeed? Investors in Mediobanca are being offered 23 new shares in MPS for every ten they hold in the target bank. Even before a slide in MPS’s share price following disclosure of its bid, that represented a frugal premium of 5%. Mediobanca calculates that by January 27th it had become a 3% discount.

In a defiant note, the target bank’s directors rejected the offer as “strongly destructive of value”. MPS argues that absorbing Mediobanca would release €700m a year of savings, representing what Luigi Lovaglio, MPS’s chief executive, describes as “an incredible strategic opportunity”. Analysts are unconvinced. They worry that any gains could be offset by the culture clash which would arise from merging an investment bank with a retail lender.

Some have also asked whether the true aim of the operation is influence over Generali, Italy’s biggest insurer, in which Mediobanca is the largest investor. There, too, Delfin and Mr Caltagirone already have sizeable stakes and are once again united in criticism of the management. The government is another critic: it has objected to Generali’s plan to join forces with Natixis, a French investment-management firm, fearing it could lead to Italian savings being allocated by foreign financiers.

A takeover of Mediobanca by MPS would, therefore, extend a skein of crossholdings that is starting to look like one that formerly concentrated power in a tiny circle of Milan-based powerbrokers. It was undone by Mario Monti in 2012. Mr Monti, who lasted just two years as prime minister, believed in free markets. In contrast, Ms Meloni is the leader of a nationalist party with protectionist instincts. ■