ARTEF Fine Art Photography Gallery, Zurich

18 Settembre 2022

Over the last two decades, society has witnessed an array of landmark design moments. Here are five new innovations from LDF’s 20th anniversary edition

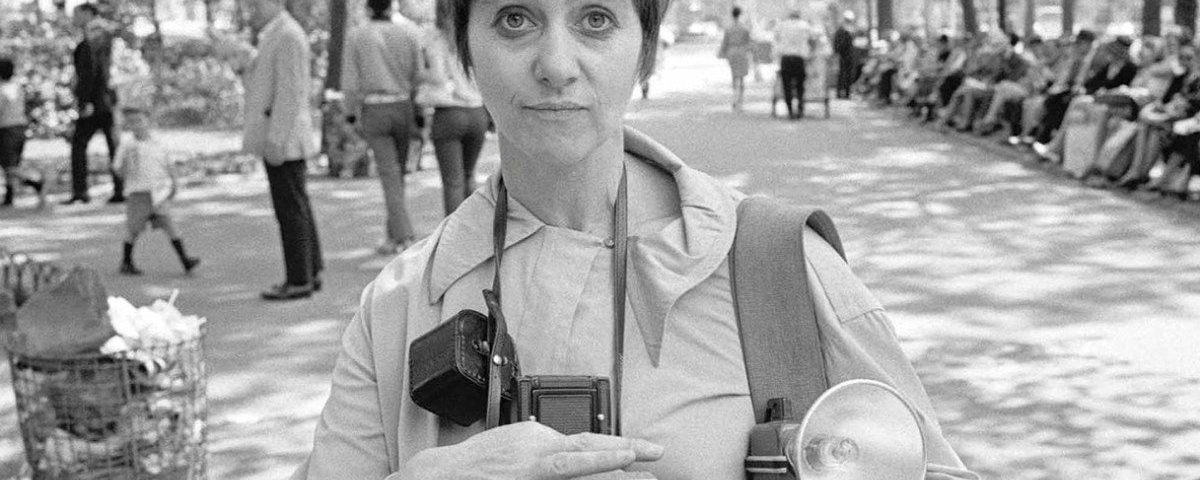

18 Settembre 2022David Zwirner Gallery in New York is restaging the photographer’s 1972 retrospective.

Diane Arbus exhibited her work only once during her lifetime, as part of a two-room photography show in 1967 with Lee Friedlander and Garry Winogrand called “New Documents” at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Arbus had a room all to herself and showed 32 photographs. One was of a smiling elderly couple, fully naked, at a New Jersey nudist camp. Another captured a boy in Central Park, vamping for the camera with a toy hand grenade. Arbus received scattered critical praise for the show — she was “a one-woman revolution,” per Newsweek — but it was not well-attended and confounded a lot of reviewers. “Sometimes, it must be added, the picture borders close to poor taste,” said a New York Times review with the title “People Seen as Curiosity.” Friedlander has called it, “The most influential photography exhibition no one ever saw.”

In May of 1971, Artforum published a small portfolio by Arbus, and one of her works — a portrait of a stone-faced boy in a straw hat, marching at a rally in support of the Vietnam War — appeared on the cover. Several other images published in the magazine are now among her most famous, including one of Eddie Carmel — “a Jewish giant,” according to Arbus’s caption — at home in the Bronx with his much smaller parents, and an eerie 1966 photograph of a pair of identical twins. Arbus introduced the portfolio with a cryptic note, describing a dream she’d had that she was on a “gilded, Cupid-encrusted” ocean liner that was on fire and slowly sinking. “There was no hope,” Arbus writes. “I was terribly elated. I could photograph anything I wanted to.” Two months later she killed herself. The next year, she had her second museum exhibition, also at MoMA.

ADVERTISEMENT

“MoMA just thought this was going to be another show,” said Jeffrey Fraenkel, the dealer who co-represents Arbus’s estate. But “it was an earthquake ,” a once-in-a-generation moment. This week, for its 50th anniversary, Fraenkel and David Zwirner gallery are restaging the exhibition at Zwirner’s West 20th Street outpost in Manhattan. They are also publishing a 500-page book of writings about Arbus called “Documents.”

It’s rare for a 50-year-old art show to be remembered with such fervor, and rarer still to attempt to re-create one down to the last work. (Approximately half of the photographs at Zwirner will be the same prints that appeared at MoMA.) The MoMA show was titled eponymously; the restaging is called, less subtly, “Cataclysm.” It was, at the time, the most highly attended solo show in MoMA’s history. Lines to get in stretched around the block. “People were really lost in front of these images, and transfixed,” said David Leiber, a partner at Zwirner. Fraenkel described discovering Arbus when he saw the pictures that ran with Robert Hughes’s review of the show in Time magazine. “It was like lightning going through my body,” he recalled.

MoMA’s Arbus show has since taken on an element of myth, but “Documents” also chronicles a significant backlash. “Rarely have I read as much nonsense as the aura of almost patronizing worship covering the work of Diane Arbus at the Museum of Modern Art,” Lou Stettner wrote in the photography magazine Camera 35.

Arbus’s family owned a Fifth Avenue department store called Russeks. Her future husband, Allan Arbus, worked in the Russeks advertising department. She started shooting pictures for the family business. In 1956, she began studying with Lisette Model, a street photographer known for her frank depictions of people in unguarded moments, who told Arbus, “Never photograph anything you are not passionately interested in.” She’d soon separate from her husband and stop working for her parents.

She supported herself with editorial assignments and became an in-demand freelancer, in particular for Harper’s Bazaar and Esquire. But Arbus sold only a few pictures while she was alive, for less than a hundred dollars each. Fraenkel believes a MoMA security guard bought one of the works from the “New Documents” show. (“I’ve had my radar up for that security guard for years,” he says.) Arbus printed her portfolio “A Box of Ten Photographs” in an edition of eight. She sold four. The buyers were: Bea Feitler, the art director of Harper’s Bazaar; the artist Jasper Johns; and the photographer Richard Avedon, who bought two, and gifted one of them to filmmaker Mike Nichols. (“The buyers are out of who’s who,” Arbus said at the time.)

As she became more serious about her practice, her concerns shifted. As A.D. Coleman wrote in an obituary in the Village Voice, Arbus was interested in “the freakishness of normalcy and the normalcy of freakishness.” About the 1972 show, Coleman wrote in The Times, “She gravitated to subjects we group under the label of ‘freaks’ … not out of any decadent search for the outré but because she saw them as heroes.”

The MoMA show was controversial. Two works were removed. One picture, “Two girls in identical raincoats,” a remarkable study in contrasts shot in Central Park in 1969, was taken down from the wall when the father of one of the young women threatened the museum with a lawsuit; he claimed Arbus had, as Fraenkel put it, “made his daughter look like a lesbian.” The other, a 1968 portrait of Viva Hoffmann, an Andy Warhol collaborator, made its subject so upset that she later told New York magazine, “A lot of horrible things have happened to me, but I consider that the worst.”

ADVERTISEMENT

Of the subjects in the MoMA show, Susan Sontag wrote, “Do they see themselves, the viewer wonders, like that? Do they know how grotesque they are?” There’s still something unsettlingly ambiguous about Arbus. Had she captured the dignity of people who had been unfairly marginalized or was she simply gawking at them? After the artist’s suicide, Harold Hayes, her editor at Esquire, noted, “Only those who have been photographed by her know what sorcery she must have employed to persuade such confrontations.”

An earlier version of a picture caption with this article, relying on information from a photo agency, misidentified the MoMA exhibition shown: It was the museum’s 1973 show “From the Picture Press,” not its 1972 exhibition “Diane Arbus.” The image has been removed. The article also misidentified a portfolio that Arbus printed of her own work; it was “A Box of Ten Photographs,” not her Artforum portfolio. The article further misstated the number of editions of the portfolio that she printed; it was eight, not 50.

M.H. Miller is a features director for T Magazine.