At the end of his first year at the architecture school of the Royal Danish Academy, Pavels Hedström went on a class trip to Japan. Hedström, a twenty-five-year-old undergraduate, revered Japanese culture and aesthetics, even though he had never visited the country. As a teen-ager growing up in rural Sweden, Hedström had been introduced to Zen meditation by his mother, Daina, and devoured manga and anime. In architecture school, Hedström was drawn to Japanese principles of design and how they applied to a world—and a profession—increasingly troubled by the climate crisis. Hedström was particularly influenced by Metabolism, a postwar Japanese architectural movement that imagined cities of the future as natural organisms: ephemeral, self-regulating, and subject to biological rhythms of growth, death, and decay. In 1977, Kisho Kurokawa, one of Metabolism’s founders, wrote, “Human society must be regarded as one part of a continuous natural entity that includes all animals and plants.”

It was the summer of 2016. In Tokyo, Hedström and his classmates visited Kurokawa’s Nakagin Capsule Tower, from 1972, which was one of the few Metabolist structures to be built. It consisted of modernist, detachable, cube-shaped modules, each prefabricated according to the dimensions of a traditional Japanese tearoom. But the Metabolist future never quite arrived. (The tower fell into disrepair and was dismantled in 2022.)

The class then travelled to the small island of Naoshima, to visit the Chichu Art Museum, a mostly subterranean concrete structure designed by Tadao Ando. The museum is dedicated to the work of three artists—Claude Monet, James Turrell, and Walter De Maria—and lets in light through geometric openings in the earth above. Hedström experienced the building as a revelation: a sequence of almost religious encounters with concrete, sky, land, and sea. “It felt like I came to the end stop of architecture,” he told me recently. The museum was astonishing. Hedström loved being there. And yet he didn’t feel good at all. “My mind was bent,” he later wrote.

Part of Hedström’s reaction stemmed from the familiar, dismaying sensation that many young artists feel upon encountering an outrageous masterpiece: Who am I trying to kid, anyway? But there was also an unease that felt particular to his generation. Hedström wanted to build a better world. At the same time, architecture was deeply implicated in what was wrong about the world. Around a third of global carbon emissions come from the construction industry and from the energy used to heat, cool, and operate buildings. Humanity is paving and enclosing the earth at an unthinkable rate. According to the International Energy Agency, an estimated 2.6 trillion square feet of new floor area will be added to global building stock between 2020 and 2060—that’s the equivalent of throwing up a New York City every month. In the brutalist beauty of the Chichu Art Museum, Hedström experienced a combination of creative and political futility. “I was somehow overwhelmed,” he recalled. “It just took my breath away, like, literally. And I got, like, starting to feel ill.”

Back home, Hedström began to suffer panic attacks. He was an avid climber, and enjoyed martial arts and calisthenics. But his body deserted him. “It was a new kind of emptiness that I never felt before,” Hedström said. “I didn’t think that I was going mad but I felt that I was going under. It was like the end of my abilities.” He moved back to Sweden, to live with his brother, Kaspars, a musician in Malmö. Hedström spent most of his time drawing and listening to music. When he tried to meditate, his ears filled with tinnitus. “I was really afraid of silence,” he said.

Hedström now ascribes his illness, which lasted slightly more than a year, to a sense of anxiety about the future of the planet—and to the delusion that he might be able to save it. “Does the world want to be saved?” Hedström asked me once. “You know, it’s a huge question.” When he returned to architecture school, he changed his approach to design, starting with a search for balance in his own body and, later, for devices that might help humans to live more intimately, and equitably, with other species. He channelled his dread into ideas that existed somewhere between solutions and warnings for the future. “It is very, very close to something that is connected to fear and to, you know, apocalypse,” he told me.

Hedström’s work is at once disturbing and alluring. He calls his process “working with playfulness around really scary shit.” He summons the action figures of his childhood—implausible machines—and casts them into a future of ecological and social distress. “It’s about actually reprogramming our minds with how we connect with nature,” he said. “I guess that’s what I want to achieve.” Hedström thinks of most architecture as “a membrane designed to protect and separate us from the rest of nature.” His intention is the opposite: he wants nonhuman life to be so close as to be inescapable. One of his devices is a hooded PVC suit and face mask—based on the gear worn to clean oil rigs—that a person shares with a colony of mealworms. The warmth and humidity inside the suit nurture the worms, which can digest certain forms of plastic, and can then be consumed, in turn, as a source of human sustenance. “Like shrimp popcorn,” Hedström says. “Really nice.”

Another of Hedström’s prototypes, the Fog-X, is a thigh-length outdoor jacket that can be converted into a shelter and repurposed, with the aid of lightweight poles, into a sail-like apparatus that collects drinking water from the air. An app provides real-time data to track fog and clouds. In February, the Fog-X won the global Lexus Design Award for young designers, beating more than two thousand entries. “Pavels is kind of like this very romantic, ‘Dune’-like character in how he and also his work presents,” Sumayya Vally, a South African architect who designed the 2021 Serpentine Pavilion and has mentored Hedström, told me. “It’s dystopian, but also very, very real.”

Paola Antonelli, the senior curator in the Museum of Modern Art’s Department of Architecture and Design, was on the jury of the Lexus award. She situated Hedström’s work in a tradition of speculative and radical architecture that began in the nineteen-sixties. Groups such as Archigram, in London, and Archizoom, in Florence, imagined walking cities and plug-in cities and “No-Stop City,” a city freed from architecture itself. They plumbed the future in order to confound the present. “Gorgeous artifacts—so a great formal elegance—that attract the eye in order to then capture the mind,” Antonelli said. “Pavels, just out of school, is kind of the son of all these designers.”

The urgency of the climate crisis makes Hedström uncomfortable with the idea of doing speculative or abstract work. “You can easily put it aside,” he said. “I want to bridge speculative design with something that would actually be a suggestion. For me, it’s really important that everything I draw should also work.” One afternoon in June, I flew to Copenhagen, where Hedström lives with his wife, Mai Sakamoto, a Danish Japanese fashion designer, who also studied at the Royal Danish Academy, and their baby daughter, Komo.

Hedström has a tendency to get lost in his thoughts. We had agreed to meet at the Nørreport metro station, but there was no sign of Hedström, and he wasn’t answering his phone. I stood in the sunshine. The city was like an advertisement for European civilization. Danish families rode past on cargo bikes. Tourists were getting drunk on pleasure boats. But it was unusually hot. It hadn’t rained for almost three weeks. The national drought index was at 9.7 out of 10. I started walking in the direction of Hedström’s apartment. When we met in the street, about half an hour later, Hedström was aglow with a faint sweat. He had recently shaved his shoulder-length hair to a buzz cut. He was wearing a blue tank top, black shorts, black boots, and a blue bucket hat. In order to find me, he had borrowed an enormous bicycle, which was the size of a pony.

In the nineties, Anthony Dunne and Fiona Raby, researchers at the Royal College of Art, in London, used the term “critical design” to describe a field that seeks to challenge, rather than affirm, the way we live now. Dunne and Raby, who now run the Designed Realities Lab, at the New School, in New York, have observed that radical design largely fell into abeyance after its heyday, in the seventies, with the triumph of market capitalism. “Reality instantly shrank, becoming one dimensional,” they have written. “There were no longer other social or political possibilities beyond capitalism for design to align itself with.”

However, the financial crisis of 2008, the ensuing decade of political instability, and the quickening, visceral damage of climate change have energized the field again. Moving away from the techno-utopian cityscapes of the past, practices such as Forensic Architecture, in London, Lateral Office, in Toronto, and Formafantasma, which is based in Milan and Rotterdam, use the methods and principles of design to reconsider everything from war crimes to timber supply chains and future urban planning in the Arctic. In a 2018 essay about teaching young designers, Dunne quoted Ursula K. Le Guin, the science-fiction writer, to express his hope that they might be “realists of a larger reality,” rather than simply problem solvers for a Western model of capitalist consumption. “What if design education’s focus on ‘making stuff real’ perpetuates everything that is wrong with current reality?” he asked.

Hedström had invited me to see “Worms of Mass Consumption,” an installation featuring his mealworm device, which he calls the Inxect Suit. The show was at a small community theatre in Sydhavn, not far from the city center. In a darkened space, three metal trays of mealworms hung from the ceiling. The worms were bathed in pink light, which turned on and off, and were feasting on Styrofoam that Hedström and his collaborators had finagled from a local recycling plant. The smell—overwhelming and ammoniac—was appalling. “It’s a big conflict at the start,” Hedström said.

Hedström has proposed factory-like systems that would feed plastic waste to mealworms on an industrial scale, but he grapples with the ethical and practical problems in doing so. (It takes a colony of three to four thousand mealworms a week to digest a coffee cup.) “It’s very capitalistic or, like, it’s a very human way of thinking,” Hedström said. It doesn’t feel like symbiosis if one of you is being farmed. Mealworms are the larvae of Tenebrio molitor, a species of darkling beetle, which is sensitive to light. As part of the exhibition, Hedström and his collaborators had attempted to use lighting to direct the worms to consume the Styrofoam in certain patterns. But it wasn’t working very well. Hedström contemplated one of the trays of heaving, quietly popping creatures. “Is it a method,” he wondered, “or is it torture?”

Since 2014, the Royal Danish Academy has offered a master’s program called Architecture and Extreme Environments. The course was founded by David Garcia, a slender, charismatic professor who worked at the studio of the British architect Norman Foster, in London, and was a partner at Henning Larsen, a well-known Danish firm, before moving into academia to agitate for architecture that meets the demands of the climate crisis. “The work that we create here is trying to cry out,” Garcia told me. “These things cannot just be put on the back burner anymore.”

When I met Garcia at the architecture school, which occupies a former naval building on the Copenhagen waterfront, the students had gone home for the summer. The Architecture and Extreme Environments studio was a promising mess of construction boots, rolled-up plans, and unusual contraptions stacked on open metal shelves. Each year, Garcia takes a group of about thirty students to spend a month in a location facing some form of ecological stress. In 2015, it was the Amazon; last year, it was Jakarta. The students spend months researching the site before building and testing a product—a flood barrier, a water-filtration system—and then proposing a related, climate-conscious building.

The increasing frequency of heat waves, wildfires, and severe flooding in Europe has altered Garcia’s sense of what they are preparing for. “The narrative of extremes has absolutely changed, only in the span of nine years. In the very beginning, it sounded like a very sensationalist title, something that happened far away,” Garcia said. “Now it’s become almost a generic understanding of many of the conditions we’re experiencing.”

Garcia cultivates an intense atmosphere in the course. Lotta E. Locklund, a recent graduate, described it to me as “a little bit of a studio flying on its own.” Locklund studied at the Southern California Institute of Architecture, or sci-Arc, in Los Angeles, before returning to Europe to complete her studies. “I think people that are drawn to the program are people that are critical of the current state of the built environment in the first place,” she said. “I think our generation of designers carries that very heavily.”

Plenty of Garcia’s graduates go on to work in public policy or for N.G.O.s. But between a third and half are hired by mainstream architecture firms. Garcia acknowledged that it was not always an easy transition. “Given how much pressure practices are under today, they just want graduates that can draw cad and bim,” Garcia said, referring to design software programs. “Very few practices, in reality, are looking for critical thinking and a critical voice that will make them grow with the times, with the urgencies of the moment. They think of that as a disruption.”

In 2022, Locklund joined Herzog & de Meuron, a celebrated Swiss practice—a decision that she is still, to some extent, wrestling with. “There is a huge identity crisis in coming out of a program such as this one,” she said. “You’re so driven to think for yourself and then you have to conform in an industry that doesn’t necessarily encourage that.”

H&dM employs five hundred and fifty people in offices from Hong Kong to San Francisco. In theory, Locklund explained, working at a major firm should give her the opportunity to influence the building industry for the better. In reality, it was difficult to challenge the preoccupations—aesthetic, political, or otherwise—of any firm’s founders. “I don’t see any chance of affecting that,” she said. “And it’s also not my place.” Locklund was grateful for a job and the imprimatur of H&dM on her résumé, but she wasn’t sure of her long-term plans. “It’s not about individual firms,” she said. “It’s more about: What is an architect’s role? Where do I fit into this architectural machine or this building-industry machine that is going on?”

Hedström met Garcia within a few days of arriving at the architecture school, as an undergraduate, in the fall of 2015. “He just wanted to go to this program from the very beginning,” Garcia said. Hedström had spent the previous three years in art schools in Sweden, moving from painting to increasingly elaborate wooden sculptures. “I started to build things,” he said. “And they got bigger and bigger.” In Copenhagen, Hedström had a profound sense of meeting his vocation. In high school, he had wanted to be a diplomat and to address climate change through international politics. In architecture, potential solutions felt closer to hand. “It’s so banal, but I really had an idea of being part of saving the world,” Hedström said. “There was a tool set for it.”

Before he fell ill, Hedström’s schoolwork had a momentous, unboundaried feel. For one early assignment, students had to make a technical 2-D drawing of an everyday object, like a pair of scissors. Hedström devised a five-minute animation of plastic bottles, arrayed infinitely inside one another, like a Mandelbrot set. For another project, students were asked to design a building where people could come together. Many of Hedström’s classmates designed cafés, or museums. Hedström proposed a combination of prison and monastery, where monks who had chosen to withdraw from society could coexist with inmates, who had been excluded from society. The complex took the shape of a huge twig and it sat on top of a residential apartment block. “The prison was extremely provocative,” Markus Oxelman, a fellow-student, recalled. It got Hedström’s classmates and professors talking. “Not like in a typical top-student way,” Oxelman said. “But kind of a weird genius, who is doing something that’s completely out of line, but it works.”

During Hedström’s first year in Garcia’s program, the class travelled to the Atacama Desert, in Chile, which is the driest place on Earth. Hedström was fascinated by the camanchaca, clouds that roll in from the Pacific and form a dense fog that yields no rain. It is thought that the Incas harvested water from trees and cacti that were able to condense the fog, and, since the fifties, there have been experiments in Chile involving fine nylon meshes to extract drinking water from the clouds. Hedström was inspired by the Namib Desert beetle, which catches fog on its abdomen, to see if a human could be empowered with similar technology. “He was very interested in this idea of autonomy,” Garcia said.

The first Fog-X prototype was a backpack that included a plexiglass dome. The dome would store water and, when the backpack unfolded, serve as a window for a small tent. “You would be able to see how much life you would have left, in terms of water,” Hedström said. In the Extreme Environments course, students make their prototypes for a few hundred dollars and see how they fare in the real world. “We don’t care if these experiments work or don’t work,” Garcia said. “It’s always accumulated knowledge.”

Hedström’s first device had fiddly aluminum poles, which buckled in the Atacama winds. He hadn’t thought enough about the soil, or about how the fog-catching net could be tethered. “Parts were bent and things were cracking,” Hedström said. He was afraid of scorpions. The camanchaca was always in the distance, cresting another mountain. When he finally managed to deploy the Fog-X in promising conditions, it collected only a few millilitres of water. (A later prototype, which he tested this spring, worked better.)

Hedström was drawn to gathering water in the Atacama in part for political reasons. Chile’s water system was privatized during the military dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet—one of a series of extreme economic experiments that fostered corruption and gouged ordinary consumers. Shortly before Garcia’s class arrived in Chile, in the fall of 2019, widespread protests erupted across the country, in response to social inequality and the rising cost of living. Hedström stayed in the mining city of Antofagasta. He watched buses of military police heading toward burning barricades. He found the reality of social unrest and being in a water-starved environment much less stressful than the idea of those things.

It was energizing, in fact. One day in the Atacama, Hedström was chasing the camanchaca with another student when their car, a two-wheel-drive pickup, got stuck in the sand. They had finished their drinking water and were out of cell-phone range. “I really remember when I started to dig under the tires,” Hedström recalled, “that this is how I would like it to be when I work as an architect.”

Hedström is the youngest of four siblings. He grew up outside the village of Stora Mellösa, in central Sweden, in a collection of Falu-red barns known locally as Castellet, or the Little Castle. Hedström’s parents were artists and teachers. Castellet was a dilapidated former community arts venue that his father, Bo, dreamed of restoring. Hedström’s childhood was free-roaming and frugal. He played in the woods a lot. “We didn’t have that much money,” he said. “At the end of the month, we were searching the sofas for coins, so I could get some candy and my father could get cigarettes.”

Castellet was in a permanent state of renovation. Bo was always at the table with a coffee and some new plans. “My mother got mad,” Hedström recalled. “You could come home and not know the way to the toilet.” (His parents separated in 2005.) Bo eventually restored Castellet’s event spaces for music and spoken-word performances. Hedström went to a Waldorf school, an experience that he disliked but which nonetheless shaped his understanding of the world. When he played, he liked to pretend that he was a businessman. He dreamed of a carport and of cycling on asphalt roads.

One morning in April, 2020, during the onset of the pandemic, Hedström felt an urge to call his father. They had a close relationship but rarely spoke on the phone. When Bo picked up, his voice sounded off. He had passed out that morning and was waiting for an ambulance. “I really feel that life is leaving me,” he told Hedström. Tests showed that Bo, who was sixty-five, had cancer that had spread to his brain, lungs, and stomach. He was given three months to live. On his first night in the hospital, Bo sketched a plan of a new building that he would like to die in.

Hedström spoke to his uncle Björn, Bo’s brother, who is an engineer, and decided to move home to build the structure. “The project was really about a vessel of life and death,” he said. Hedström took over his father’s studio. In the mornings, he continued his architecture studies, and in the afternoons and evenings he and Björn worked on the new, single-story building, a short distance away, in the garden. “I almost had the title ‘architect,’ ” Hedström said. “I got the respect in the family.”

The project was called Vänd mot Norr, or Facing North. (Bo was from northern Sweden.) The design incorporated a small pier, which reminded Bo of one that he fished from as a child. The building itself was simple and small—a little more than five hundred square feet—with a living space, a kitchen, and a bathroom, all made from wood and glass. The outside was black, with a long pent roof, and inside the timber was bare and unpainted. Hedström felt like he was realizing an image in his father’s mind, while engaging with the essential questions of architecture—making a space for human life and death—for the first time. The building’s northerly aspect meant that sunlight would not hit the windows and there would be no reflections. “It’s the most transparent way of getting in touch with nature,” Hedström said.

Hedström and his family had a budget of around nine thousand dollars. They called in friends and favors. The yard was filled with music while they worked. The gatherings reminded Hedström of his childhood. “The most beautiful part was the social aspect,” he said. Bo rested in a virtually inaccessible bedroom in Castellet, at the end of a narrow corridor. In the evenings, he would emerge to eat supper, sit, and talk. Jacob Schill, a friend of Hedström’s, came and helped out for a week. “I don’t think blissful is the right word, but it was a very idyllic Swedish summer,” he said. “And his dad lies in this room, and he could open the window and see out to the building.” Schill compared the construction to a Viking ritual: “You go with your boat. He went with his house.”

When Hedström, Kaspars, and two friends carried Bo out from his room, on a stretcher, a herd of cows started lowing in a field. Hedström slept with his father on his first night in the new building. Bo said that it was his best sleep since he had fallen ill. The rest of the family brought in mattresses, so they could be together, and lit a huge fire outside the windows which burned through the short August night. “Then he started to cross,” Hedström said. Bo died two days later. “It was used for one day of life and two days of transition,” Hedström said, of the new building. “And it was extremely satisfying.”

At the time, Hedström’s elder sister, Marta, was pregnant with her first child. Facing North enabled his family to convene and to act, to combine grief with purpose, death with making. Previously, Hedström had been occupied with architecture’s power to recast the environment. Now he learned its social force as well. “It just changed my mind in terms of what architecture can do,” Hedström said. He made his father’s coffin from wood left over from the house. Once Bo was cremated, Kaspars made an urn for the ashes from the same material.

The Inxect Suit was the prototype for Hedström’s thesis project. Garcia’s class could not go abroad during the winter of 2021, because of the pandemic, but they were allowed to travel within the Kingdom of Denmark, which includes the Faroe Islands, a windswept archipelago in the North Atlantic, midway between Norway and Iceland. To make the assignment more extreme, Garcia set his class the challenge of designing for the islands in the year 2100. Fish products make up ninety-five per cent of Faroese exports. By 2050, according to the World Economic Forum, there will be more plastic than fish, by weight, in the oceans. Hedström imagined a new economy for the islands, built around the rearing of insects—a low-carbon form of protein—and the decomposition of plastic waste.

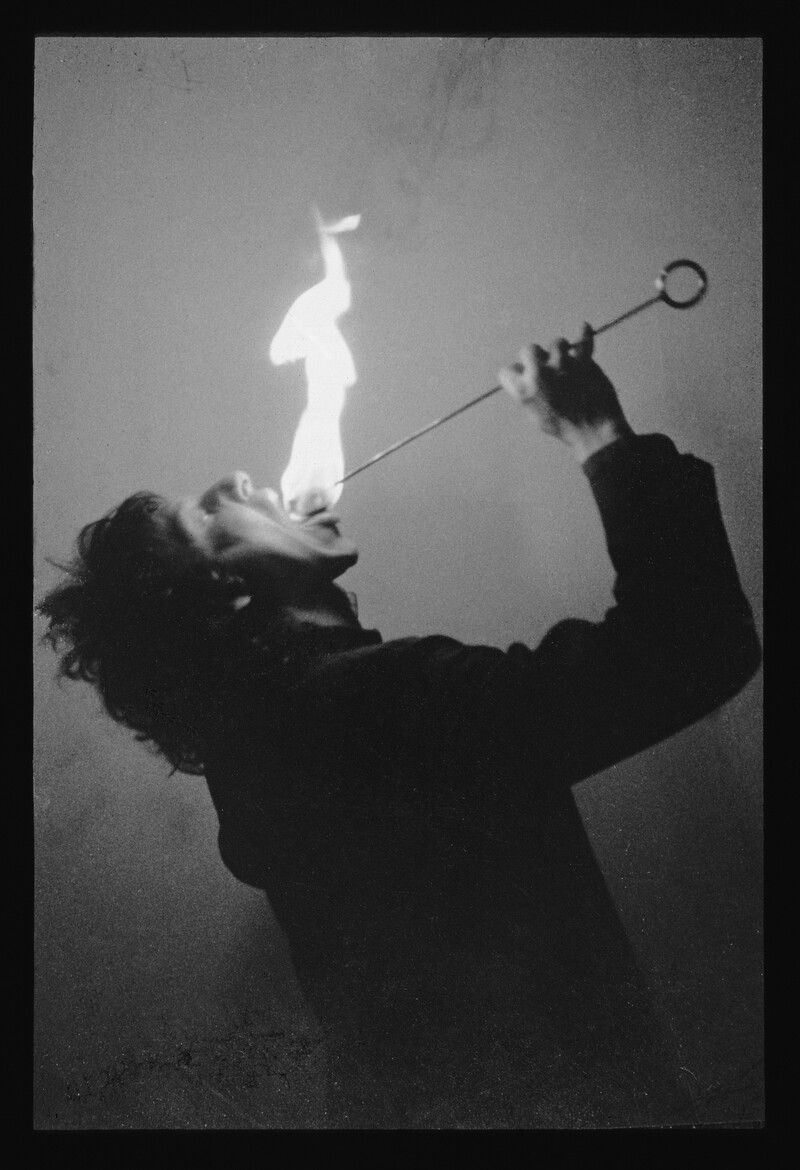

Hedström stayed in a house on Streymoy, the largest of the Faroes, and explored the capital, Tórshavn, in his orange, hooded mealworm suit. A badge on his right arm read “Inxects Mission 1. Plastic Proteins.” The temperature, humidity, and CO2 levels inside the suit were shown on electronic displays mounted on the chest. The worms crawled about, chewing on blocks of polystyrene in a transparent chamber on Hedström’s torso. People were unsure how to react. That December, the Faroe Islands were undergoing their fourth wave of coronavirus infections. (During the pandemic, equipment used to screen salmon farms for viruses was repurposed to test for covid.) “And there was this hazmat guy walking around, and cables connected,” he said. “I think they were trying to figure out whether to be afraid.”

When Hedström received his first consignment of mealworms in the mail, he was disgusted and somewhat afraid. But he forced his hand into the worms and left it there, until he felt comfortable. When he was testing the suit on Streymoy, he concluded that the worms didn’t like steep hills, which made them tumble about. In order to keep them warm, and less jostled, Hedström developed a sequence of movements from Tai Chi. “This idea of having another species that directs you, your behavior and your movement—that really impressed me,” he said. One day, Hedström performed Tai Chi for the worms on a set of forbidding cliffs, while Garcia filmed him with a drone. At the end of a month in the Faroes, Hedström starved his mealworms—to expel any plastic from their digestive systems—before freezing them, boiling them, and then frying them for tacos that he served to Garcia and the rest of the class. “It was part of the commitment,” he said. “I was quite excited when I was eating them.”

For his final presentation at architecture school, Hedström proposed Inxect Island, an apartment complex built around mealworm farming, sustained by ocean-borne plastic, on a decommissioned oil rig moored outside Tórshavn. It was a vision, for 2100, of circular, low-carbon living, fuelled by the polluted sea. Hedström’s design took the form of a rising spiral of modular living units, bamboo “photosynthesis parks,” and “protein/bioplastic production” zones, with an outdoor meditation space. The structure resembled a mechanical tree, and was hung with fourteen escape ramps, for lifeboats.

One of Hedström’s external assessors was Søren Øllgaard, a partner at Henning Larsen, which was founded by one of Denmark’s leading twentieth-century architects, in 1959. (Larsen, who was known as the Master of Light, died in 2013.) The machine-like aesthetic of Hedström’s project made Øllgaard think immediately of Archigram and other, earlier forms of radical design. “I was amazed by his work. I was amazed when he came in,” he recalled. Øllgaard described Hedström to me as a “Viking in a spacesuit.” “It’s kind of a metamorphosis of conception and person and project,” he said. “Everything is one big idea, one big cloud of urgency.”

Øllgaard offered Hedström a job. Henning Larsen has seven hundred and fifty staff members, and offices in Hong Kong, New York, and Berlin. Øllgaard hoped that Hedström could infuse the practice with some of his terror—and creativity—for the future. “I think we do too little utopian projects,” Øllgaard told me. “Part of us should talk about, not necessarily the next thing that we need to build, but what is right to build.”

Hedström hesitated before accepting. In Denmark, Henning Larsen was known for its long association with the country’s leading industrialist families and for exporting Danish modernist design to all corners of the world. (One of Larsen’s best-known buildings is the Saudi Ministry of Foreign Affairs, in Riyadh.) In 2019, the firm became part of the Ramboll Group, a global engineering consultancy, where it accounts for five per cent of annual revenues of two billion dollars. Hedström wasn’t sure how his ideas would fit in with a corporate environment. “I was so critical,” he told me. “I’m really disturbed by the reality of the business.”

On his first day in the office, Hedström wore orange pants and a green snake amulet, designed by Sakamoto. “I think it was really important for me to make a stand in terms of ‘I’m not buying into the identity. I’m here to contribute and learn,’ ” he said. A few hours later, he was assigned to work on a conventional apartment-and-office block in downtown Stockholm. “I get the pitch for the project,” Hedström said, “and I started to watch on my time.” According to Hedström, he was later put on a team for a proposed forty-story tower in the business district of Brisbane, Australia, with the working title Meanjin, the Indigenous Turrbal name for the promontory on which much of the city is built. The façade had a cascade of plants and greenery, to evoke a rain forest. Hedström felt that no one on the team engaged meaningfully with the ecological or social dimensions of the site. His own skyscraper sketches weren’t convincing at all. “We never talked to any Indigenous people, and this really upset me,” he said. “You know, we were in the heart of capitalism.” (A spokesperson for Henning Larsen said that the firm was working with creative consultants, including Blaklash, an Aboriginal design agency, to engage with the traditional custodians of the land.)

Every Henning Larsen project met sincere and exacting environmental standards. This was Denmark, after all. But that wasn’t bold enough for Hedström or, in his view, for our ecological moment. “We were building for, like, business as usual. And I think that was the main problem,” Hedström said. “Because, you know, the challenge that we are standing in front of, it’s so urgent and it’s so alarming.” Hedström describes his time in “the sticky business of architecture” as his most valuable learning experience in the field, after the death of his father. He remains close to Øllgaard. But, stuck in front of a computer screen, he came to fear for his imagination. “People working crazy hours and breaking their backs, I got to experience the bodily, the physical experience of working that way. And that also got me really skeptical,” he said. “I became a pretty bad architect, actually.”

Hedström lost his job last December. Sakamoto was five months pregnant. When I caught up with Øllgaard, he had just finished breakfast at his summer house, outside Copenhagen. He acknowledged that there was a gap between the sustainability goals of firms like Henning Larsen and what ends up getting built. “The younger generation, they get extremely frustrated that we have this kind of high-end strategy but we are not doing it,” Øllgaard said. “The problem is that, if we should follow it completely, we should stop seventy per cent of all our projects. . . . But, I mean, they kind of don’t care. And that’s, of course, the force of the young generation. They have got the courage for not caring.”

Yet Øllgaard was thinking more and more about the buildings he actually wanted to see in the world. “I’ve been working more than thirty years and I’m also a little sick of doing the wrong thing,” he said. “If I should continue working, I’m not going to do, like, fifty thousand square metres of concrete building in Paris with aluminum and steel.” He paused. “It’s coming to an end.”

The Danish summer was extreme this year. For a month, it barely rained. The national drought index reached 10. Fields turned yellow and midsummer bonfires were scaled down, or cancelled. Then it rained. It was the wettest July since records began, in 1874, as floods and storms swept the Baltic. I was walking with Hedström through Copenhagen on the day the weather turned. The air above the city became bruised and heavy. We took shelter from the deluge under a café awning. Hedström was telling me the story of his illness and his recovery, and about his daily meditation. “It’s really hard. . . . It brings the thoughts up, that you then can deal with,” he said. “It’s the opposite of being enlightened—it’s being confronted.”

Since the birth of Komo, this spring, Hedström has felt torn between conflicting priorities: supporting his young family and helping design a future worth living in for a child born in 2023. “It goes from day to day,” he said. “Sometimes I’m getting a bit stressed.” When Hedström received the Lexus Design Award, in April, at Milan Design Week, he used his ten-minute audience with Antonelli, the design curator at moma, to ask her advice on how to make a living. “What Pavels has gone through is very understandable,” Antonelli told me. “There is going to be a learning curve for the world to understand what to make of these designers. They are extremely important, really fundamental, but they don’t yet have a slot in the organigram of companies, of institutions, and governments.”

Hedström is planning to open his own studio, and has been talking to companies in Japan about consultancy work, and to researchers in Chile about developing the Fog-X project. Last month, he visited the port of Cromarty Firth, in northern Scotland, for a tour of decommissioned oil rigs. Vally, the South African architect who has mentored Hedström, is a year younger than he. She grew up in Johannesburg, where she founded her own practice, Counterspace, to explore African and Islamic forms of design. “With me, or someone like Pavels . . . the ideas are important, and people believe in them, but they don’t know what to do with you,” Vally said. “We know deeply that we need systemic change, but we have to make it ourselves.”

The next morning, Hedström planned to show me the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, in Humlebæk, about twenty miles north of Copenhagen. Unfortunately, we caught a train to Holbæk instead, which is about fifty miles in the wrong direction. On our way back, he told me about his next idea, which was to connect the Inxect Suit and the Fog-X jacket to four more prototype devices—supplying health care, energy, shelter, and education—to fashion a utopian collective that he is calling Village 1. Hedström explained that he wanted to go beyond the individual to investigate the social dynamics of a climate-damaged world.

“This is the next exploration,” Hedström said. “It’s dismantling the complexity of a civilization or a society into the most fundamental resources and demands.” He was thinking about refugee and migrant camps, which he believes resemble the cities of tomorrow—vast, organic settlements of people on the move—and designing a network of devices that can serve people there. “It’s a bit like in Zen. You strip the mind down, to understand the core of what is important,” Hedström had told me, that first night in Copenhagen. “I guess it’s getting to the core.” ♦