The Demon Slayers

28 Luglio 2024

La (ri)forma della città

28 Luglio 2024Cairokee, idols of disillusioned Arab youth

The Egyptian rock band, known for their politically committed songs, performed for the first time in Lebanon on the maritime stage of the Byblos festival, in front of a captivated audience in search of meaning.

OLJ / By Emmanuel HADDAD

Tiit, tiit! Small electric golf cars criss-cross the old town of Jbeil, carrying tourists who have come to take a boat trip and admire the Phoenician ruins. But on this Friday, 19 July, visitors to the 1,000-year-old city are not there to enjoy the conservation of its heritage.

Alia* is walking with a group of friends down the narrow alleyway decorated with the Chez Pepe restaurant that leads to the port, where the Byblos Festival stage rises majestically from the water’s edge. Wearing a jacket in the colors of the Palestinian keffiyeh, the Yemeni student who is studying in Lebanon feels privileged to be here: “I’m so happy to finally be able to see Cairokee. I’ve been following them since they started out during the Egyptian revolution and I love them because their songs carry a message. They say out loud what we think but can’t necessarily say,’ she says, visibly moved.

‘They know how to find the right words’

By inviting the group, an icon of the Egyptian revolution and the new standard-bearer of the Palestinian cause with its song Telk Qadeya (This is a cause), the Byblos Festival Committee is keeping a promise made on May 28 by its president Raphael Sfeir to L’Orient-Le Jour to take part in “a form of cultural resistance.” This is certainly the opinion of Alia, for whom Lebanon remains “the most open country in the region in terms of freedom of expression.” In her opinion, “Palestine is resisting in its own way, and Lebanon is doing so through its cultural offering.”

Where other festivals, such as Beiteddine, have chosen not to hold an edition “in this year of genocidal war in Palestine” and the ongoing cross-border conflict in southern Lebanon, the Byblos Festival has sought to offer a festive respite to “a people attached to the culture of life” as caretaker Tourism Minister Walid Nassar said when he presented the festival’s program.

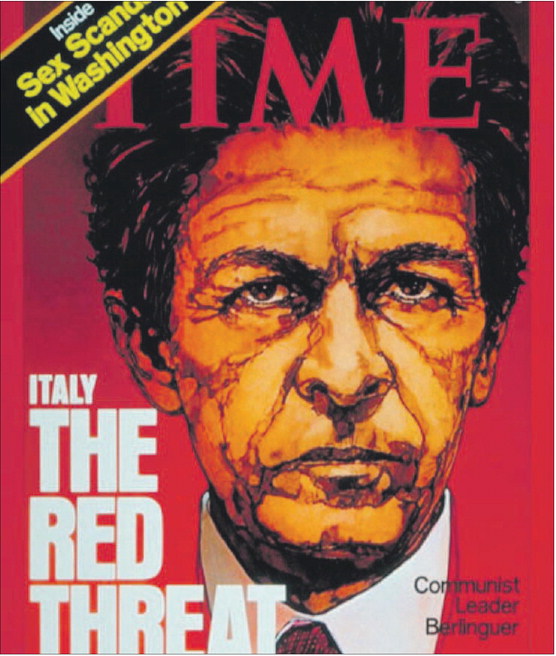

“We are fighting for life,” says Ali, paraphrasing the former secretary-general of the Lebanese Communist Party, Georges Haoui, when asked if he finds it strange to go to a festival in a country at war. “That’s Lebanon,” agrees Reem, who is beside him. “Resistance through weapons and resistance through culture are two sides of the same battle,” continues the journalism student who has come from Saida to listen to his idols.

“I’ve been following them since they started out. They say what we all think, but above all they know how to find the right words,” Ali adds. “What’s more, they’re with the cause and so are we,” he continues, pointing to the Palestinian flag covering his friend’s shoulders.

Speaking before the festival doors open, Christine, 29, who works in the theatre world, says, “The subjects they talk about, the revolution, the Intifada, all that unites our generation.”

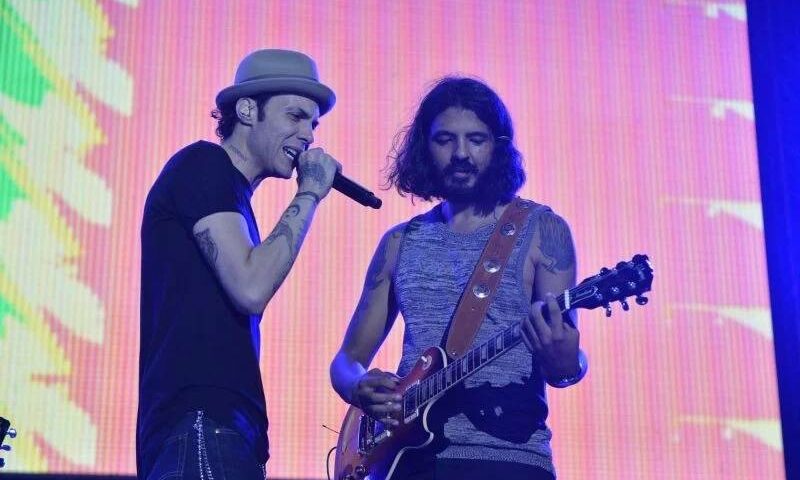

A lion, the logo of the band Cairokee, appeared on the black screen and the audience roared to the rhythm of Sherif Hawary’s first guitar riffs.

“This is the first time we’ve played in Lebanon, we’re very happy,: says singer Amir Eid, provoking an outpouring of joy.

As soon as he starts a melody, the whole audience stands up and sings in tune, captivated. His lyrics, full of puns and double meanings, are on the lips of fans, most of them in their 20s. And they are denunciatory and disillusioned. “I feel anxious and uncertain,” begins the song Dinosaur. Thirteen years after singing Sout el Horeya (Voice of Freedom) and Ya el Midan (O You, the Square) in tribute to the Tahrir Square revolution that toppled Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak, Amir sings about those people “in the street who look like zombies’ and this period in the Arab world when ‘while the world moves forward, we live in the Stone Age.'”

Fighting for a better tomorrow

In Egypt, the fall of dictator Mubarak cleared the way for another authoritarian leader, Abdel Fattah al-Sissi. And in the region, the Arab Spring and its cries of hope have been followed by an authoritarian winter in which dissenting voices are stifled one after the other. “Days gone by, happy and blessed times, I don’t exist in tomorrow, I’m only myself in memories,” continues Amir in Basrah w atoh (My mind wanders and I get lost).

As well as the lyrics capturing the bitterness of an Arab youth in the midst of a counter-revolutionary backlash, the performance’s visual work plunges the audience further into a dystopian, hallucinatory universe. Images of a hyena-faced concert-goer being devoured by a giant robotic cat, a dove trying to get out of its cage only to be crushed by a skull and crossbones, and caricatures of American presidents looking like puppets vociferating imperialist rhetoric all scroll by.

Suddenly, the Statue of Liberty appears on a blood-red screen. Like Janus, the face of the devil completes its double face. Amir plugs in his acoustic guitar, the audience falls silent and the first words of Telk Qadiya ring out over the port of Byblos. “He saves sea turtles, he kills human animals. It’s one cause, and it’s another.” Amir’s suave voice denounces the Western “double standard” in the face of the atrocities taking place in Gaza, and suddenly keffiyehs are brandished in the audience, with everyone making the peace sign with their hands. By the end of the song, the emotion was palpable. “It’s a cause, and it’s a struggle,” Amir concludes, the word “kifah,” struggle, filling the screen and heralding a future in which Arab youth may yet be able to exist.