The footage is grainy, but the shape of the plunging body is unmistakable. A middle-aged man dressed in a white shirt, dark grey trousers and black leather shoes falls directly down in a seated position, facing the wall of a medieval alleyway. As his legs hit the wet cobblestones below, his body bounces back a metre, then falls back with arms outstretched behind his head.

The time reads 7.59pm on March 6 2013. Over the next 22 minutes, the CCTV camera captures the head and arms writhing, eventually falling still. It takes nearly an hour for paramedics to arrive on the scene. During that time, two figures enter the cul-de-sac. One, wearing a blue puffer jacket and a light flat cap, approaches the body, apparently checking for signs of life. After a few moments, the pair slink away back into the shadows.

David Rossi was 51 when he died. He was the communications director at the oldest bank in the world, Monte dei Paschi di Siena, and the bank was under threat. A multibillion-euro scandal threatened to bring more than five and a half centuries of rich history to an end.

To the people of Siena, Monte dei Paschi is not just a bank. It is the city’s largest employer, affectionately known as Babbo Monte, or Daddy Monte. From almost the moment of its founding, in 1472, two decades before Christopher Columbus set sail on his maiden voyage to the Americas, Monte dei Paschi’s story has been a study in the very purpose of banking. It has served as a charity for Siena’s poor, a benefactor to the city’s civic institutions, a patron of the arts, a financier for Tuscan agricultural development, a money pot for the local nobility and an aggressive industry consolidator, run in the interests of global investors. Often it has played more than one of these roles at the same time.

“Its very existence is a form of propaganda for Siena,” said Mario Ascheri, a professor of medieval Italy and author of a history of the city. “Having the Monte is a sign that the city cares for its people.”

In the early 2000s, the bank’s charitable foundation was spending €150mn a year in and around Siena — from supporting the local university and sports teams, to paying for childcare and ambulance services. It was involved in nearly every facet of Sienese life. But in recent years, Siena’s Babbo has dealt the city a series of crushing blows. Since 2008, after years of rapid growth that neglected its founding ideals, the bank’s fortunes have collapsed, and, with them, those of the city it has supported for hundreds of years.

Ten days before he died, Rossi’s home was searched by police investigating a series of shady and complex financial transactions. Rossi was under pressure to co-operate with their investigation. The stress of that situation, as well as the recent death of Rossi’s father, led investigators to conclude this was a death by suicide.

But Rossi’s family were unconvinced. And, over the years, evidence has emerged that adds weight to their suspicions. An autopsy revealed cuts and bruising on Rossi’s arms and wrists, suggesting a struggle before his fall. Red marks in the shape of fingerprints were discovered on his upper arm. He had suffered a deep triangular gash to the back of his head, consistent with being struck by a sharp object. His office window, three storeys up, was open, and it was assumed that Rossi jumped from there. But the trajectory of his fall, combined with his curious backward-facing seated position, suggested he might have been pushed from a higher floor of the 14th-century stone fortress that served as the bank’s headquarters.

For more than a decade, the mystery surrounding Rossi’s death has hung over the city of Siena and its bank. Haunted by its scandal-ridden past, Monte dei Paschi’s future now looks as uncertain as at any time since 1472. The Italian government, which bailed out the bank in 2017, hopes to relinquish its remaining stake by the end of this year. The likely outcome is a takeover of the bank by a larger rival with no connection to Siena — a disaster for the city it has built and nurtured for centuries.

At the turn of the millennium, Monte dei Paschi was at the peak of its powers, with more than four million customers and close to 2,000 branches globally, including outposts in New York, London and Singapore. Newly listed, it had an international investor base, which was demanding quarterly profits and fast growth. The world’s oldest bank began engaging in the cut-and-thrust markets of dealmaking and financial engineering.

It is hard to pinpoint the exact moment when things began to go wrong, but Pierluigi Piccini, a former mayor of Siena who once worked for the bank, put his finger on Monte dei Paschi’s acquisition of its Padua-based rival, Banca Antonveneta, in 2007. “Before the Antonveneta acquisition, [Monte dei Paschi] was one of the best capitalised banks in Italy,” he told me. “The financial problems started from that point.”

The decision to buy Banca Antonveneta from the Spanish bank Santander, for €9bn, just as the clouds of the financial crisis began to gather over Europe, would indeed go down as one of the worst mis-steps in the history of banking.

Santander had bought Banca Antonveneta only a few months before for two-thirds of what Monte dei Paschi agreed to pay. Santander’s chair, Emilio Botín, sounded almost embarrassed as he told shareholders about how his bank was making a €3.4bn profit from the deal. To make matters worse, Monte dei Paschi had agreed to pay cash, rather than use its own shares. The management team were soon scrambling to raise the funds without affecting the bank’s capital position. They launched a series of retail bond sales, essentially borrowing money from households and small businesses to pay for the deal.

It soon transpired that very little due diligence had been done on the deal. Monte dei Paschi had paid massively over the odds for a badly indebted business with little opportunity for expansion. It had raised €1bn from Wall Street’s JPMorgan to contribute towards paying for Antonveneta through a type of bond that would convert into equity if the borrower ran into trouble. Italy’s central bank said Monte dei Paschi did not inform it about this transaction.

Monte dei Paschi’s foundation also claimed it was unaware of the deal. The charitable arm would soon be called upon to provide capital for the transaction. The foundation had been set up in 1995 in the run-up to Monte dei Paschi’s listing on the Italian stock market to continue its charitable duties and become the main owner of the bank, with shares representing one-quarter of its market value being publicly traded in 1999.

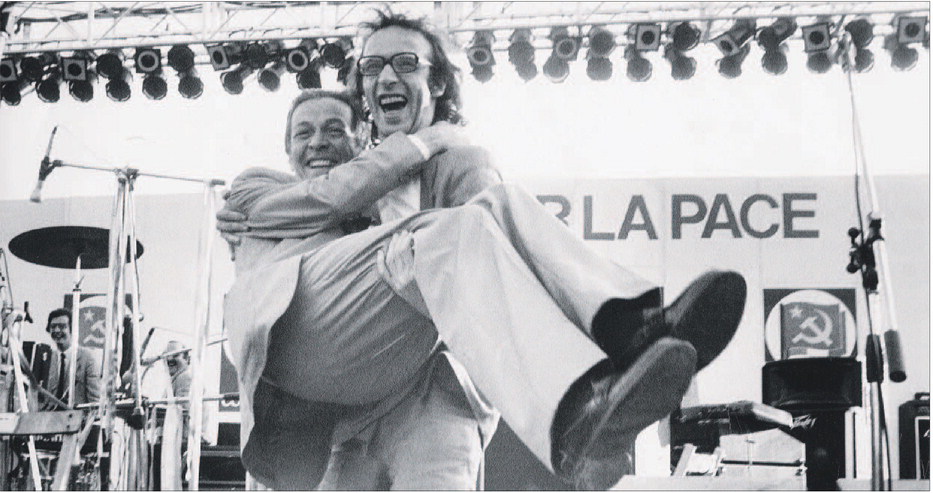

Since the second world war, Siena had been a leftwing stronghold, with practically every mayor for half a century coming from the communist or socialist parties. Their views on the social function of a bank had shaped Monte dei Paschi’s identity. Its commitment to supporting the city was deep. The foundation had created two new departments at the city’s university, including the only one in Italy dedicated to banking, which trained hundreds of future Monte dei Paschi employees. From the 1980s onwards, its executives moved freely on to the local council, while several mayors of the city had close ties with the bank and its trade unions.

Mayor Piccini had been widely tipped to take over as president of the foundation in 2001, but Giuseppe Mussari, a Calabrian, was chosen instead. Five years later, Mussari became president of Monte dei Paschi, and set the bank on a course of rapid growth, doubling its profits in six years — a growth spurt that would have serious consequences.

In the wake of the disastrous Antonveneta deal, the foundation was forced to bail out the bank, cutting off its funding to many of Siena’s cultural and sporting organisations. The city’s football and basketball teams both went bankrupt in 2014, and were forced to start again in much lower leagues. In the decade after the deal, the foundation’s assets dropped from €8bn to €200mn, while its stake in the bank fell from 46 per cent to 0.003 per cent. The city had lost control of Babbo Monte, the benefactor with whom its fortunes were tied.

Filippo Alloatti, an executive at fund manager Federated Hermes, which invests in Monte dei Paschi’s bonds, understands the complicated relationship between the city and its bank better than most. “My family has lived in the Tuscan countryside just outside Siena for hundreds of years, but when we go into the city, we are still seen as foreigners,” he said. “To understand the bank, you have to go deep into medieval history.”

Perched on three hills among the vineyards and olive groves of the Chianti region of Tuscany, the medieval city of Siena was founded by the Etruscans. With no natural water supply, the city was unable to develop industry, so banking and commerce became the basis of the economy.

During the early Renaissance, banking flourished in Italy, with the city states of Florence, Genoa, Milan and Siena underpinning much of European trade. Sienese bankers established a reputation for tenacity, especially when collecting “donations” from the heads of churches and abbeys across Europe, which could be funnelled to Rome.

In the 1470s, around the time Leonardo da Vinci was making a name for himself as a painter in nearby Florence, Siena established a monte di pietà, a sort of charitable pawnbroker that lent money to citizens against a security. Usury was regarded as a sin by the Catholic Church, so lending was mostly carried out by Jewish financiers, who often charged interest of up to 40 per cent or more. In an attempt to get around this, Franciscan friars exploited a loophole by charging a fee corresponding with the costs of managing the account. The monte system spread across Italy.

Siena’s monte was set up by the city authorities. Under its statutes, signed on March 4 1472, it was meant to ensure that “poor or wretched or needy persons [were] aided and assisted in their wants and needs”. The monte began with 5,000 florins, raised from tax revenues on wine, salt, meat, fish and vegetables. Borrowers were charged 7.5 per cent interest a year, which paid the costs. As collateral, they typically handed over jewellery or clothing, with early ledgers listing items such as “six little earrings” and “two Spanish-style cloaks”. The headquarters was, and still is, the Salimbeni Palace, an imposing fortress in the city centre, known to locals as La Rocca.

At first, the monte operated locally and shied away from taking risks. The city’s authorities had already seen the collapse of huge Italian banking institutions, which had overstretched themselves and imploded. But the monte did not see itself as merely a charity. It also became a powerful patron of the arts, almost single-handedly financing the Sienese School of painting. “You have to admire the ancient Sienese people,” said Ascheri, the historian. “There is an astonishing line of continuity in this love for art, even in bad periods. They always tried to create beautiful things.”

In the second half of the 16th century, Siena came under the rule of the Medicis, the powerful Florentine family, who began transforming the monte into a public bank that would be known as Monte dei Paschi, taking its name from the pastures surrounding the city. The bank began rapidly increasing its lending. Its biggest customers were local farmers, looking to buy new livestock, build barns or simply tide themselves over until the next harvest. As the lending book grew, so did opportunities for embezzlement: in 1623, local authorities discovered that 20 per cent of the bank’s capital had been misappropriated. Among those suspected of theft were the treasurer, several knights and a theologian. After a 14-month trial, which involved the use of torture, several perpetrators were sentenced to death.

The Medicis ordered the bank to adopt a more professional approach. Customers wanting loans were now required to hand over a deposit, typically deeds to land. Increasingly Siena’s nobility looked to Monte dei Paschi to finance major events in their lives. Rich families borrowed from the bank to pay their daughters’ dowries.

By the 18th century, Siena had fallen on hard times. Monte dei Paschi suffered too, narrowly avoiding bankruptcy in 1711. A few years later, the bank’s charitable arm, known as Monte Pio, was found to have a shortfall of 20,000 scudi and two local noblemen were blamed for mismanagement. One, who belonged to an order of knights aligned with the Medicis, was pardoned. His less fortunate accomplice was decapitated.

At this point, the bank was barely profitable. It had overstretched itself by financing most of the city’s public works. But it also suffered from persistent malpractice. Its administrators were often the very same nobles whose families were borrowing heavily from its coffers. Local magistrates were unwilling to pursue guilty bank officials.

Having financed the restoration of Siena following an earthquake in 1798, Monte dei Paschi gradually began to recover throughout the 19th century. It helped finance Italy’s wars of independence against the Austrian empire, and was given responsibility for collecting taxes. In the decade after Italian unification, deposits doubled to 22mn lira. Yet it was still unable to shake its legacy of mismanagement. On two occasions in the late 19th century it was bailed out by the state.

In the Piazza Salimbeni outside La Rocca, Monte dei Paschi’s headquarters, stands the imposing marble statue of 18th-century Sienese economist Sallustio Bandini. On a hot May morning this year, he glared down at groups of wandering tourists.

Their guide raised an umbrella, directing them along the Via Banchi di Sopra, one of Siena’s main shopping streets. Above the shop fronts hung colourful flags with the medieval insignia of local contrade, or city wards, which were deep in preparation for the upcoming Palio bareback horse race. The 17 contrade all owe a debt to the monte, in acknowledgment of which, on the morning of the races, representatives dressed in heraldic ceremonial outfits descend on the piazza to pay homage to the institution that has supported them for centuries.

To one side of the street, under a gothic arch, a narrow passage joined an alleyway along the back. It was here that David Rossi fell to his death. Draped along the wall was a banner reading Verità per David — truth for David. Among the many messages of support scribbled on the sign were notes calling for “justice to prevail” and “No Omertá!!!” Eleven years after his death, Rossi’s family are still looking for answers.

“It seemed so obvious on that night that David had killed himself that the police didn’t do a thorough investigation,” said an employee who was in the building at the time. He recalled a chaotic evening where paramedics did not know how to access the alleyway behind the headquarters, and staff and police trampled in and out of Rossi’s office, contaminating the crime scene. “Now we may never know what happened to the poor guy.”

There were other mysteries. The soles of Rossi’s shoes were marked with flecks of fresh white paint and varnish, consistent with the renovation work taking place on the top levels of the building. No decorating was happening on the third floor. When police searched Rossi’s office, they found three crumpled suicide notes in the bin. Handwriting experts concluded Rossi was their author, but that they had probably been written under duress.

One, supposedly addressed to his wife, read: “Ciao, Toni, my love. I’m sorry.” But Rossi’s widow, Antonella, said he always referred to her by her full name. Then there was an email apparently sent by Rossi to his boss reading: “This evening I’m going to kill myself, I’m serious. Help me!!!” Investigators later found that it had been created in the bank’s email server the morning after his death.

But perhaps the detail that is hardest to explain was an unidentified call received by Rossi’s mobile phone at 8.33pm — just over half an hour after he fell to his death. At around this time, the CCTV footage shows his wristwatch, without its strap, come tumbling down from the same direction his body had fallen, according to an investigation commissioned by his family.

The story has never been far from the public’s imagination. After flaws were exposed in their initial investigation, Siena’s police came under pressure from politicians and prosecutors to re-examine crucial evidence. Rossi’s body was exhumed in 2016 and special detectives investigated the bank’s servers, trying to figure out the inconsistencies over the timing of emails. Three years ago, a special parliamentary inquiry into the case was established in Rome.

The death attracted much speculation in Italy, with accusations of corruption and sex parties among Siena’s elite, as well as suggested links to organised crime. Earlier this year, it emerged that a man suspected of killing three sex workers in Rome, who has ties to the Camorra crime syndicate, claimed in a 2019 interview with police to have been responsible for Rossi’s death.

In the course of their investigation, police identified the two figures captured on CCTV who entered the alleyway after Rossi’s fall. They were co-workers who were the first to find his body and call the ambulance, and they were not treated as suspects. But Rossi’s family were still unconvinced.

Rossi’s brother, Ranieri, remembers his brother’s passion for journalism. At the age of nine, David produced his own newspaper, which he distributed among his friends in the neighbourhood. An early career in media led to press officer roles in local government, then at Monte dei Paschi’s foundation, and eventually at the bank itself. “He was a quiet and thoughtful guy, a man of boundless culture,” Ranieri said.

On March 6, the anniversary of Rossi’s fall, his stepdaughter, Carolina Orlandi, lay down on the cobblestones of the Piazza Santi Apostoli in Rome. Now aged 30, Orlandi was staging a demonstration to raise awareness of her family’s search for justice. Fellow protesters held up three-foot high photos from Rossi’s autopsy, showing the cuts to his head and limbs, while others displayed a banner for the assembled press.

The pig’s head, left at the gates of a suburban Sienese home and still dripping with blood, had all the symbolism of a Godfather movie. It was an unsubtle message to a Monte dei Paschi executive that the bank’s decision to cut funding to the city had not gone down well with the locals. It was 2014, and the bank’s fortunes had gone from bad to worse.

“We had stopped paying dividends to the foundation and for all of us who had joined from outside the town it was tough,” recalled the executive, who wished to remain anonymous. “We were viewed as people who were tearing the bank apart, robbing them of the crown jewel of the local economy. When we pulled the sponsorship of the football team and basketball team, we received death threats.”

The Antonveneta deal was not the only example of bad management in the bank’s years of relentless growth. In 2002, Monte dei Paschi had accumulated a large stake in a rival Italian bank that would go on to become Intesa Sanpaolo. Eager to do more deals, Monte dei Paschi’s management team contacted investment bankers at Deutsche Bank and asked for a way of unlocking cash from the stake, while still being able to benefit if Intesa Sanpaolo’s share price rose. For a hefty fee, Deutsche’s derivatives specialists came up with a structure that they called “Santorini”.

When the financial crisis hit Europe, Italy’s lenders were hit hard. The unrepaid loans swelled on their balance sheets and losses mounted. Monte dei Paschi was not immune, and neither was Intesa Sanpaolo. The Santorini trade had gone spectacularly wrong. While it was designed to allow Monte dei Paschi to benefit if Intesa Sanpaolo’s shares went up, Monte dei Paschi would make a loss if those shares tanked. Intesa’s stock lost three-quarters of its value in less than two years and Monte dei Paschi was down €367mn.

If the bank published such a big loss in its annual accounts, it was at risk of needing a bailout and takeover by Italian authorities. So, in a bid to obscure it, Monte dei Paschi once again turned to Deutsche’s derivatives experts. This time the Deutsche team devised a more complex extension to the Santorini trade whereby Monte dei Paschi would book a gain on its 2009 accounts, which would mask the €367mn hit, but drip-feed a bigger loss over several years. The German lender once again received a chunky fee for its services.

Monte dei Paschi also struck a derivatives deal, dubbed “Alexandria”, with Japanese investment bank Nomura. Under this transaction, Nomura packaged up several hedges Monte dei Paschi had in its Italian government bond portfolio to protect against volatility, creating a single trade that breached Monte dei Paschi’s regulatory limits for exposure to a single counterparty.

When these secret transactions were eventually exposed in late 2012, it was revealed that Monte dei Paschi was on the hook for €730mn thanks to its dalliance with arcane financial structures. The bank’s share price began to crater and the government was forced to bail it out with a series of multibillion-euro cash injections. By 2017, it was clear that half-baked refinancings would not work, and so the finance ministry handed over €5.4bn in exchange for taking a 70 per cent stake. It was Italy’s biggest bank nationalisation since the 1930s.

Two years later, a Milan court convicted 13 bankers at Monte dei Paschi, Deutsche Bank and Nomura, including Monte dei Paschi’s former chair Giuseppe Mussari and chief executive Antonio Vigni, as well as the two foreign lenders, of colluding to hide more than €2bn of losses with secret derivatives trades. The executives faced the prospect of lengthy prison sentences, while the two foreign banks were fined a combined €152mn. Monte dei Paschi had earlier reached a €10.6mn court settlement over the hidden losses. Separately, another former Monte dei Paschi chief executive, Fabrizio Viola, and chair Alessandro Profumo were convicted of false accounting and market manipulation and handed six-year prison sentences.

But the Italian government still had a problem. It was the majority owner of the weakest bank in Europe, which stress tests had shown would be wiped out in the event of a severe economic downturn. It was also essentially propping up the biggest employer in Tuscany.

Under the terms of the bailout, the finance ministry had to agree to conditions set out by the European Commission that Monte dei Paschi would be returned to private ownership by the end of 2021. With six months to go, the government hit upon a sale by offering very generous terms to UniCredit, Italy’s second-biggest bank.

The government advisers would be in for a tough round of negotiations. UniCredit’s chief executive, Andrea Orcel, was Europe’s best-known dealmaker. During his time as an investment banker at Merrill Lynch, he had orchestrated many of the biggest bank takeovers, including advising Santander on its over-the-odds sale of Antonveneta, a deal that had earned Orcel few friends in Siena. The government had offered very generous terms, providing up to €2.5bn of capital to support the deal and freeing UniCredit from Monte dei Paschi’s book of bad loans and legal risks. But even so, UniCredit pulled out with just a few weeks before the deadline. The government had run out of time.

Luigi Lovaglio does not fit the mould of a hard-charging bank executive. Softly spoken, with a slight build, his thick moustache complements his bushy eyebrows. In his office overlooking Via Francigena, the ancient pilgrimage route from Canterbury to Rome that bisects Siena, Renaissance art hangs from the walls.

Lovaglio was approached to take over as chief executive of Monte dei Paschi in 2022. The disappointment of the failed UniCredit takeover had sent the finance ministry into a tailspin. It knew it needed to act fast to end the purgatory of state ownership and ensure Monte dei Paschi did not wither away, putting 20,000 people out of work. Having missed the deadline set by the European Commission, the finance ministry asked for an extension and began working to a new date. When officials offered the role to Lovaglio, the mission was simple: return Monte dei Paschi to the private sector by the end of 2024.

Lovaglio accepted the proposal and in February 2022 he stepped into La Rocca for his first day in the job. “From that moment, I felt the weight of history on my shoulders,” he told me. “It was very clear that the bank should not fail after more than 550 years.” Lovaglio believed that to put the bank back on to a firmer footing he needed to slash spending, jettisoning one-fifth of the workforce, about 4,000 staff. But to pay for the restructuring, he needed to ask shareholders for a further €2.5bn in the bank’s seventh capital raise in 14 years.

With the funds raised, Monte dei Paschi’s fortunes began to turn. First, Deutsche Bank, Nomura and the 13 bank executives accused of trying to hide losses had their convictions quashed. Profumo and Viola also had their convictions for market manipulation and false accounting overturned. It was now much less likely that Monte dei Paschi would get dragged into further lawsuits, which allowed the bank to cut back €466mn on the amount it had set aside to cover legal risks.

At the same time, banks across Europe and the US were benefiting from a sustained rise in central bank interest rates. One of the main sources of bank profits is the difference in interest between what they pay out on deposits and receive on loans. The speed with which central banks raised their rates between 2022 and 2023 turbocharged Monte dei Paschi’s profits. By the end of the year, it had generated a record €2bn of earnings and was able to pay shareholders their first dividend in 13 years. That gave Monte dei Paschi’s share price a much-needed boost, and the Italian government a good excuse to sell Monte dei Paschi shares in the market, reducing its stake to just over 25 per cent, which it plans to divest fully by the end of this year.

The upturn in fortunes has allowed Lovaglio to start thinking about the future. The bank is now much more attractive as a takeover target than it was three years ago, when UniCredit walked away from a deal packed with incentives. Weeks after I met Lovaglio in May, Giancarlo Giorgetti, Italy’s economy minister, announced that his government was trying to find a deal to merge its remaining stake in Monte dei Paschi with another bank as a way of returning the lender to private hands in a stronger position. Lovaglio, who calls himself a “civil servant”, believes the bank will endure, despite what he calls an “unavoidable consolidation process”. Meanwhile, central banks look set to start cutting their rates in coming months and additional taxes on Italian banks are also rumoured.

In Siena, the local government is moving on from the loss of its vital source of funding. It has been forced to be more entrepreneurial, developing its tourism sector to attract visitors throughout the year, not just in the busy summer months, and encouraging investment in a plan to make the surrounding area a pharmaceuticals hub. Costs have been cut right back, and underused properties sold off or rented out.

The unanswered questions surrounding Rossi’s death continue to haunt the bank and the wider city. Rossi’s family are still craving closure and Ranieri is exasperated. “We have been trying to get the truth out for 11 years [after] two investigations and a parliamentary commission . . . Usually in these cases the truth comes out after 50 years,” he said.

A takeover will bring an end to the independence of Monte dei Paschi and may irreparably sever its links to its home city, even if its famous name will survive. “The Monte dei Paschi brand is too valuable, and in the right hands might even become a strong source of income,” said Piccini, the former city mayor. “But unfortunately it will not help to develop and sustain Siena as it has done for more than five and a half centuries.”

Owen Walker is the FT’s European banking correspondent

Follow @FTMag to find out about our latest stories first and subscribe to our podcast Life and Art wherever you listen