The pastor is pacing back and forth, a cordless microphone in one hand, the other extended before him. He says, “This is the awakening the American church has been waiting on,” and keeps pacing. He has readied himself before taking the elevated stage, donning a paisley shirt, top button undone, and speaks now from the wood pulpit of his revival tent. There are evils hiding among the congregation, the pastor continues, unseen devils that must be named and expelled. “I renounce you, Satan,” he says, “and all of your demons.” On his command, those demons will be cast out by the power of Jesus: an exorcism en masse. His voice works up to a pulsing staccato, listing the lurking devils. “Yoga . . . psychic hotlines . . . every voodoo curse, out, out right now in Jesus’ name!” he says, “spirits from healing crystals come out, spirits from dream catchers come out . . . up and out!” These unholy spirits must all depart and flee far away. “Out, out, out!”

I look from the stage to the audience. Everything is silent. Could the incantation not be working? Then comes a shriek from the back, pitched somewhere between agony and ecstasy: “Aiiiiiiiiiiiii!” Other howls join across the room now, an eerie call-and-response. Chairs reposition themselves as bodies flail and slump to the ground. A bodybuilder in a tank top wobbles and collapses, his frame colliding with mine; another man breaks into a nosebleed, red drops splattering the floor.

It is a dark and swampy night outside Nashville, and thousands have gathered for deliverance from that which haunts them. The preacher is Greg Locke, a right-wing firebrand who, over the past three years, has plunged into the world of demonology, hosting at his ministry, Global Vision Bible Church, two conventions devoted to the subject in as many years. A cast of visiting preachers is scheduled to grace the stage and minister to the afflicted; other attendees will have the chance to learn something about performing exorcisms themselves, commanding demons to come out . . . out . . . out. The revelry starts early in the morning and continues past midnight.

If the scene has the sepia-toned feel of yesteryear—a sawdust revival with baptisms in a horse trough—then the organizers have done their job well. The tableau, when understood fully, is an artful, choreographed performance. On the Global Vision grounds, notices inform newcomers that, by showing up, they consent to being recorded by the half dozen cameras that swirl through the crowd, making of the audience an impromptu cast; the revival itself, a movie shoot.

Two filmmakers with Locke Media flank the stage. A third trains his lens on the face of a man who winces and twitches with his eyes closed. Nearby, an old woman thrashes and claws at the floor. Her face contorts in a snarl. One church staffer presses a Bible to her forehead while another daubs her stomach with a pocket-size vial of holy oil.

Two volunteers huddle for a diagnosis. “Is it Leviathan?” one asks another.

“Python,” the second responds.

The first nods, all business, then turns to the distressed woman. “Unhinge your fangs from her, in Jesus’ name! And take your venom with you, in Jesus’ name!”

Fluttering above the sweat-filled scrum is a video drone. It drops down for a closer shot.

Americans crave spectacle, in all matters, and exorcisms like this are today experiencing a season of growth. We Americans are drawn to those things that feel somehow both novel and ancient, old dreams and nightmares made new. Polling is fairly consistent, heathens be damned: roughly half of this country believes in the existence of demons and the ability of such spirits to possess humans. The gloomy pandemic years saw a new demand for enterprising religious figures with a remedy. And why not? Who would deny that this cursed land is in need of a deep cleanse with a power washer? This, our country of suburban satanic panics, active-shooter drills, and jump-scare franchises, of mob riots, hollowed-out downtowns, and tech paranoias. The vibes are foul. And lo, a cavalry of screen-ready revivalists has arrived to wage the End Times war against the satanic infantry. Theirs is spiritual warfare with the algorithm in mind, exorcisms that come with online subscription plans and TikTok and Facebook schematics, whose videos carry click-worthy titles like: “She Was TORMENTED By DEMONIC WITCHCRAFT SPIRITS!,” “Can Demons READ OUR THOUGHTS?,” and “DEMONS leaving people on a ZOOM call. Check it out!” These media ministers livestream and cross-post, they produce movies, write how-to books, go on national tours. When this team of ghost-busting, devil-thrashing creators comes together for events, which they do a few times a year, they even have a supergroup brand name: the Demon Slayers. Last year, Locke released Come Out in Jesus Name, his first feature-length film devoted to this subject, and is now at work on a sequel. Backstage in Tennessee, one exorcist says to another, “We need to saturate the market.” America the haunted, God shed His limelight on thee.

To understand this demonic swell is to understand its mediated spirit. Which is why I came to work for Locke Media and the Demon Slayers last summer, to help stage one of their conferences. Organizers anticipated a crowd of more than ten thousand, and their predictions were not far off. With a team of volunteers, I managed the crowd, lugged equipment, and worked backstage with the revivalists as they coordinated acts. I joined editorial meetings with the filmmakers. I set up merch tables as exorcists signed books for starry-eyed fans. And, once the demons started raging, I was in the throng, among the trembling bodies and whirring cameras . . . If an exorcism happens in the Tennessee woods and no one is filming, did it even happen?

Before he was putting out exorcist movies, Locke wrestled with his own demons. He was born in Donelson, a Nashville suburb, and spent his youth running afoul of the law, racking up half a dozen arrests for small-time crimes. His misdeeds landed him in a Christian home for wayward youth in nearby Murfreesboro, where he came to Jesus and, in time, found he had a knack for ministry. As a teenager, Locke secured a regular slot on local radio to preach.

At thirty, Locke founded his own church, where he showed an early flair for the theatrical. He biked cross-country to raise church funds. He lived four days straight in a scissor lift to solicit donations for the homeless. He released a rap song (emcee name, Rev Rymz) about the horrors of child trafficking. Later, Locke dabbled in social media, posting shaky, fire-and-brimstone video manifestos on Facebook. When the Supreme Court legalized same-sex marriage in 2015, Locke filmed an angry response. “It just went stupid viral,” he says now. “Just boom-boom-boom.” In another clip, from 2016, he stood in front of a Target ranting about the perverts and pedophiles who, he said, would exploit a new any-gender bathroom policy. “The controversial stuff,” he says, “really drove traffic.”

In 2016, Locke met a former journalist and fitness buff named Wayne Caparas. On top of launching a chain of health clubs, Caparas had tried his hand at a series of evangelical enterprises, such as staging biblical pageants and putting out his own pop-gospel album. The two met at a get-out-the-evangelical-vote revival in Las Vegas. In the neon glow of that city, Caparas came to believe their encounter was prophetic. He approached the pastor and said, “We’re supposed to do major things in media.” And indeed it came to pass. Together, they would launch Locke Media.

As COVID-19 spread and most churches closed their doors, Locke sharpened his messaging. The pastor joined other COVID-policy dissidents in calling the virus a government hoax. He banned masks from his church and dissuaded congregants from getting vaccinated. In his podcast from that time (its tagline: “Faith, Family, and Politics”), Locke interviewed fellow travelers like Dinesh D’Souza and Dog the Bounty Hunter; in sermons, he described an unholy plot that was unfurling across the country, pitting an evil Joe Biden and Kamala Harris against God-fearing congregations such as Global Vision. The church accepted virtually every press query and welcomed as many gawkers and gigglers and how-dare-you-sirs as would fit. Whatever it takes, Caparas remembers thinking. Membership ballooned and, to accommodate the growing crowds, the church put up a series of old-timey canvas tents with sawdust floors. “I wanted to keep that sweaty revival feel,” Locke says. After the 2020 election, he used his pulpit to cheer the Stop the Steal campaign, and on January 6, he was near the Capitol steps in Washington to deliver a prayer, bullhorn in hand.

Left: Greg Locke. Right: A Sunday-morning service at Global Vision Bible Church

Much of Locke’s appeal lies in his presentation as an old-school, over-the-top pastor with a country twang. To fans and foes alike, he comes across as an outrageous yahoo, and he knows it, a Chick tract come to life for internet virality. Forget Bible thumping; Locke once literally fastened a Bible to a bat and pummeled a pink dollhouse onstage. There are Lockeisms that one can collect over time, free-association flourishes that approach something like hellfire Beat poetry, Kerouac by way of Van Impe. “Away with this lukewarm, namby-pamby, Tickle Me Elmo, gummy-bear Christianity that we have in this nation,” he’ll riff, or rag on that “hokeypokey, nice, sweet, wonderful, rosy-posy, unicorn-Skittles, cotton-candy stuff” going on at some competitor’s church.

At the height of the pandemic, Locke’s sermons reached a Manichaean crescendo, complete with visions of QAnon tunnels and Hollywood cabals. Yet, when the dust settled, these could feel like unrealized nightmares, the products of an abstract spiritual war fought somewhere out of sight. Even progressive watchdogs that had been monitoring Locke grew bored. “I think he got addicted to the outrage cycle,” a Right Wing Watch researcher said. “We don’t want to be part of this nonsense anymore.” Trump was not reinstated; the Storm did not make landfall. So Locke set his sights closer, warming to the notion that he might battle demons locally, casting them out right there in the tent.

The most popular scripture among the Slayers may be from Mark 16, wherein a miraculously resurrected Jesus appears to his disciples, delivering a message that is at once dare and promise:

And these signs shall follow them that believe; In my name shall they cast out devils; they shall speak with new tongues; They shall take up serpents; and if they drink any deadly thing, it shall not hurt them; they shall lay hands on the sick, and they shall recover.

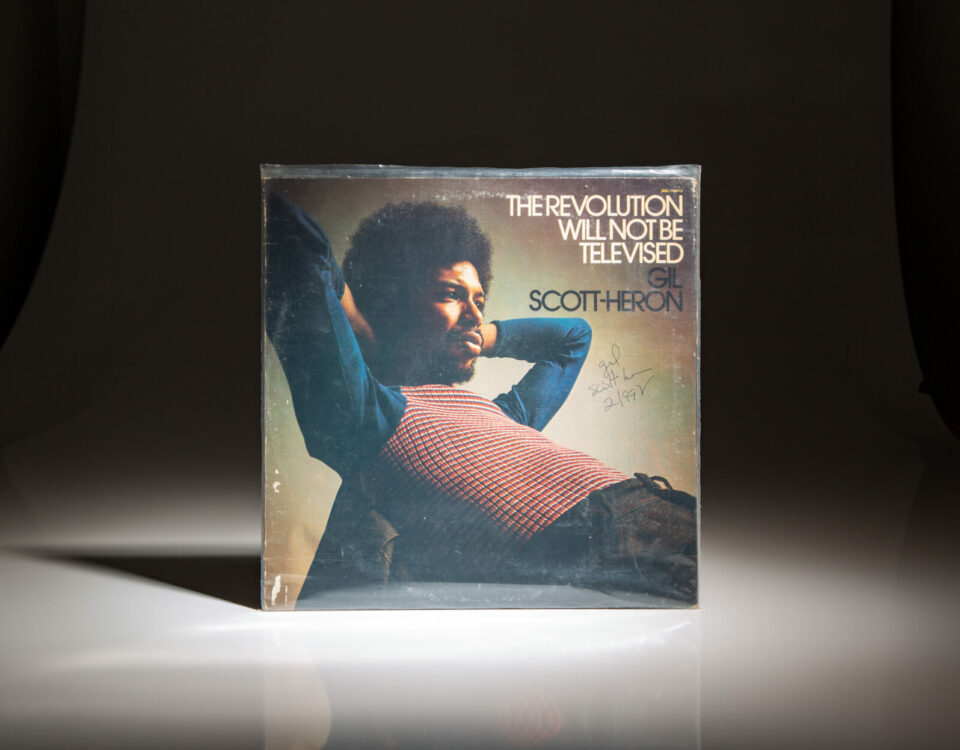

Yet, while the Bible is still the best-selling book of all time, the Slayers owe their devil-casting popularity to more recent twentieth- and twenty-first-century happenings. The cosmic yearnings of the long Sixties—think Age of Aquarius be-ins, Jesus-freak coffee klatches—let out a flood of books, broadcasts, and films devoted to all manner of supernatural subjects. Blockbusters like The Exorcist canonized the character of the devil-dueling priest, and Michelle Remembers, a creepy bestseller about ritual cult abuse, spurred the satanic panic of the Eighties. The evangelical marketplace brimmed with works of Christian horror, like those of the prolific Frank Peretti, who penned page-turners about demons lurking in small-town America. And while Pentecostals had demonstrated interest in demon-casting since the movement’s early-twentieth-century stirrings, it wasn’t until many years later that the subject received such focused attention. For some, the word “exorcism” carried an unpleasant whiff of the papacy, and they gravitated toward alternate terms, like “deliverance”; others, pragmatically, would not be bogged down by technicalities. Evangelists like Derek Prince, Win Worley, and John Wimber authored user-friendly how-tos (see Battling the Hosts of Hell: Diary of an Exorcist or They Shall Expel Demons) that became touchstones for generations of seekers wishing to roll up their sleeves and do spiritual war.

The doldrums of the lockdown can feel a world away now, but pause to remember how, in those isolated months, things felt up for grabs, both claustrophobic and wide-open with possibility. While some were bleaching shopping bags, streaming vanlife adventures, posting blobs of sourdough, or Zooming siblings in for Thanksgiving, others were exploring darker, more exotic realms. Online, a host of experimental, upstart wonder-workers were finding new audiences with eye-catching content about all things demonic. Among them were people like Vlad Savchuk, a minister in the Pacific Northwest who had spent years as a youth pastor, building his church’s YouTube presence. During the spring of 2020, he saw the popularity of his sermons on topics like curses and dark magic skyrocket. “There’s that hunger that exists within people for the spiritual stuff,” Savchuk says. He began releasing content to meet the moment. “You pretty much have a microphone, you have a YouTube,” he says, “and if people share it enough, you can become an overnight sensation.”

A Saturday-evening intercessory prayer service at Global Vision Bible Church

Others were realizing the same thing. Take, for example, Isaiah Saldivar (“went from atheist to casting out demons in his living room,” a social-media promo reads) or Alexander Pagani (“apostolic Bible teacher with keen insight into the realm of the demonic”). An ex-lawman and MMA athlete named Daniel Adams (“From Cage Fighter to Jesus Freak”) filmed man-on-the-street exorcisms in Florida. As a type, there is something of the frontier sheriff or noir detective in the exorcist, someone who has rubbed up against seamy outlaws and knows their wiles. The exorcist carries himself with a weary swagger; the exorcist is . . . badass. This new outfit swapped notes and collaborated often and took to calling themselves the Demon Slayers. It was fun, a bit tongue-in-cheek. The moniker, hatched in a group chat, referred first to a small core but grew to include an extended universe of players. Members of the collective were boosted on more old-school platforms like It’s Supernatural!, a long-running TV program hosted by the televangelist Sid Roth. Charisma Media, an influential Pentecostal publisher and podcast hub, would sign deals with at least three of the Demon Slayer crew. “As a publishing house, we knew that we had success in that genre,” Charisma’s owner, Stephen Strang, told me. It was a simple enough calculus. “So, as any publisher would be, we’re open to other books on that topic.”

As Locke experimented with deliverance at his church, his media team developed their feature-length film to capture the Holy Ghost transformation. The movie, they decided, would be something of a demonologist’s bildungsroman, with Locke’s personal arc as the backbone. Caparas recruited two Nashville filmmakers, Eddie Lamberg and Tim Romero, who had worked together on documentaries for Trinity Broadcasting Network, and a younger cameraman, Julian Franco, who once worked for YouTube. Caparas recalled staging church plays of the Passion of Christ (“Passion plays are reality stories,” he says), while Franco drew inspiration from shows of his youth, like VH1’s Behind the Music. Lamberg and Romero brainstormed as filming went on, writing plot points on note cards, arranging and rearranging them obsessively. “Oh, this is a horror story,” Romero remembers thinking. The stakes were life and death. “We’re talking about people being tormented by demonic presence and people losing their minds.”

Their film would also quickly sketch out modern religious history, encapsulating what we may call the Pentecostalization of American Christianity. Locke came up as a Baptist, part of a group that historically shied away from things like exorcisms, holding to the belief that such wonder-working activities ceased in modern times. But over the past sixty-plus years, practices once associated with older Pentecostal churches—glossolalia, faith healing, and the casting out of demons—began seeping through denominational borders and flourished across the country, a trend that has grown only more pronounced. While much has been made of the decline of religious life in America, we have also seen the explosion of this Spirit-filled style of worship, with about half of all younger churchgoers now attending these types of charismatic services.

Like a heist flick, Come Out in Jesus Name introduces each Demon Slayer in turn and builds to their inevitable collaboration at an exorcism bonanza in Locke’s Tennessee tent. The parting lines are reserved for Locke, who makes the case that his entire career has culminated in this moment. “Controversy built our platform, but it was never about the controversy,” he says, tears welling in his eyes. “God built our platform for deliverance.” Through Fathom Events, a company perhaps best known for The Chosen, the movie screened nationwide last spring. On a budget of $400,000, it grossed $2.5 million at the box office, despite showing for only three nights, and ranked among the distributor’s top films of the year. “It was a very, very successful movie for us,” Ray Nutt, Fathom’s CEO, told me. “At the end of the day, what’s it going to take to get somebody off their couch on a weekday night or a Sunday night and come to the movie theater? This kind of thing.”

The Locke Media headquarters sits in a squat strip mall a ten-minute drive from the Global Vision church. Its building is marked outside with the church’s logo: a blue ball of flame, inspired by an image that came to Locke in a dream about the growing fire of religious revival. (He also tattooed the logo on his right forearm.) Framed newspaper clippings and covers of Locke’s books hang in the foyer. In the main studio, there is an oval, newsroom-looking desk lit by overhead lights.

It’s midafternoon when Locke arrives at the studio to film an interview with Charisma Media. The publishing house had rereleased two of Locke’s earlier books and, that day, was launching his latest, Cast It Out. Pagani, the Bronx pastor, has his own book to promote and is piped in onscreen for a conversation with Locke, who gives the audience practical advice about battling demons.

The two take questions from the livestream viewers, and Pagani pauses intermittently to remind them to order now. “You are going to need this for your arsenal,” Pagani says, sometimes clapping or doing jazz hands to punctuate the dialogue. Displayed behind Locke is the poster for their first film, and they plug the upcoming conference, where the Demon Slayers will reunite.

The interview comes to a close, and the team engages in a bit of postgame analysis. “Holy cow, that was great!” one staffer says. Pagani is quiet for a moment, thinking. “Asking controversial questions can be good,” he says, “or else it can feel a little redundant.” Then the group bows in prayer.

A Sunday-evening monthly mass-deliverance service (top) and a Saturday-evening intercessory prayer service (bottom) at Global Vision Bible Church

The sun beats down on us as we work in the Global Vision parking lot, preparing for the weekend’s festivities. The church property is a sloping, eighteen-acre plot of land that contains the main tent, a prefab where the church holds school, a small building for the Spanish-speaking contingent, and administrative offices. We roll chairs out on a trolley and line them up as straight as possible in the shaded area beneath a second tent, erected to accommodate the expected crowd.

I work alongside a church staffer named Austin who has just come back from a meeting about his teenage son, who recently underwent a bumpy exorcism. Austin’s backstory is a troubled one, including infidelity, losing custody of his kids, and a brief period of institutionalization. Now, he tells me, his child has been talking about suicide, a potential sign of some persistent demonic oppression, even after a series of exorcisms. Austin says, “He’s still got some things to release.”

As it turns out, the deliverance business may not be a one-and-done matter. There are lingering doubts, faint concerns of more demons to be diagnosed and cast out. A distempered heart leaves portals open through which a spirit may pounce. Like buying a CrossFit membership to keep off the belly flab or seeing that therapist who keeps excavating childhood traumas, this is a lifelong relationship, a thing of commitment and sweat and never-ending vigilance. Demons may sneak into one’s body at any moment if allowed, through a fleeting glance at PornHub, by playfully rolling a Dungeons & Dragons die, by idly pausing to look at a Lil Nas X video. Neither are the demons distant foes; they lurk in loved ones and peers, in friends and next-door neighbors, in our very bodies.

The Locke Media bus departing for Chicago (top) and the studio at Locke Media headquarters (bottom)

Teams of employees and volunteers buzz about the grounds. Among them is a young father named Corey Traeger, pushing a sleeping baby in a stroller while another of his sons crawls nearby. During downtime, members of the staff trade exorcism stories like fishing yarns. There was the woman whose eyes turned inky black. Another who levitated off the floor. In the throes of deliverance, the demon-tormented might bite staffers’ fingers and hands and need to be restrained. “I’ve seen small children overpower grown men,” Traeger tells me. One man, overtaken by a spirit, fled the church, got into his car, and careened into a ditch. They crawl like cats. Squawk like birds. Emit strange odors and fluids. Rudi Schirr, another volunteer, retells his own deliverance: “I cried, I yawned, I farted,” he says. “It can come out of any orifice.” His eyes go muddy, unfocused in recollection. “I sometimes wonder, why didn’t I manifest harder? Maybe there’s more inside me.”

Here they come: the crowd. They drive bumper-stickered campers, rattling cars, and school buses. The dress code is somewhere between Appalachian country fair and Burning Man psychedelia: sandals and army boots, tank tops and baggy denim overalls, rainbow-colored cowboy hats, cutoff jeans, camo caps, topknots, mohawks, braided beards, pocket shofroth, and dozens of event-appropriate tees: demon terrorist, revival is war, and smack the devil in the mouth. Many have been Demon Slayer fans for years, and here (at last!) is an opportunity to see the stars offscreen. To mark the occasion, the audience will do its own ad hoc documentation, wielding selfie sticks and digital cameras. Food trucks sputter to life in the back lot next to the bouncy castle, selling açai bowls, pizza, and fragrant grilled meats.

I step away to join production assistants for a meeting in which Caparas dispenses our official lanyards and Locke Media shirts. He reminds us to keep our phones nearby, where instructions will appear in a group chat throughout the weekend.

We go around the circle to give brief introductions. After I’ve gone, Caparas interjects, with some pride: “And he’s Jewish!” A woman to my right lets out a little chirp of excitement: “Jewish!” She extends her arms and envelopes me in a hug. “We haven’t given up on you, dear.”

I’m a welcome addition, but there is some question about whether I ought to partake in the exorcisms themselves. Will I be able to cast out a devil? “The theology is a little squidgy,” Caparas says. “Go for it.” I’m an oddity of sorts: a reporter who has flown in from the coast. But Caparas pats me on the back to let me know I am also a Locke Media peer, a laborer in the shared trade of content creation. I, like him, know the pitfalls and pleasures of storytelling, the magical sleight of hand, trimming for time, cropping for impact; I also must absorb the strangeness of life and mold it into a narrative.

By midday, the tent is opened to the public, and hundreds stream inside, where the band is at work on guitar, keys, and drums. Colored stage lights fade in and out, and lyrics are displayed on huge screens:

If He did it for me, He can do it for you

Get up, get up, get up

Get up out of that grave

Get up, get up, get up

Get up out of that grave

This is the soundtrack of demon battling: well-known evangelical tunes popularized by studios like Hillsong, Jesus Image, and Bethel, funky and beloved Spotify-available jams ably covered by the house band. It’s impossible not to bob along.

An abandoned church near Mount Juliet

Several ministers arrive quietly, aided by security, and sneak past the tent crowd. They reunite and kibitz in the air-conditioned hospitality room. “It’s gonna break out,” the exorcist Saldivar says and gives a little whistle. “People are gonna be screaming.” The minister Jenny Weaver recalls a spat she had with haters online. Someone commented on a post to complain that, unlike the Demon Slayers, Jesus never promoted books, conferences, things like that. Weaver is incredulous. “Jesus didn’t sell books?” she says. “No! He had scrolls.”

After some time, the Demon Slayers and crew members come together for a preshow prayer. Caparas has a camera slung around his neck. “Getting some of the behind-the-scenes relationships,” a cameraman whispers to me. The crew follows Locke as he marches to the stage for an opening sermon.

The Tennessee heat is stifling, even as the sun dips below the trees, and it takes its toll. The tent soon has a locker-room aroma, and people fan themselves sluggishly with paper plates and Bibles. A big droplet of something wet and mysterious falls on my head. I think, at first, that I must be imagining it, but the sides of the tent are actually sagging, beading up with condensation. Cameramen must pause periodically to wipe off their lenses, and word circulates that a man has fainted from exhaustion in the parking lot. Speakers rotate onstage, and there is a rousing set of worship songs, but it becomes clear, mid-evening, that the full mass exorcism will not take place just yet. The devil isn’t going anywhere. The audience disbands, looking bummed but also relieved to escape to air-conditioned cars.

Aminister hoists above his head a medieval axe that looks, for a moment, like it may topple into the crowd. He is a heavyset man named Henry Shaffer, who grips, one-handed, the deadly instrument he has brought to display. “Make me a battle axe!” he says. The custom blade glimmers menacingly under the stage lights. “Make me a weapon of war!” Part of the promise of this conference, underlined by several speakers, is that attendees will not only experience deliverance but may also learn to cast out demons themselves and take up arms in the war at hand. “I do have a Ph.D.,” Shaffer says. “I praise . . . him . . . daily!” He warns that painted fingernails on boys are signs that the youth are not just gender-bending but demon-inhabited. “They already want our children,” he says. One of the advised first steps in an exorcism is to identify exactly what evil spirit is present. After this, the afflicted must renounce whatever deed has opened themselves up to spiritual attack. A middle-aged woman, balancing a dog-eared Bible and her notepad, nods and writes: ask demon what name.

The Demon Slayers have new merchandise to sell and assemble tables for meet and greets. Lines snake through the tent. A trio approaches Locke to ask him to pray for a family member whose car has fizzled out en route to the tent. He obliges, beginning: “Lord, if you can part the Red Sea, you can use this broken vehicle . . . ” Then they pose for a quick picture. Behind them is another fan, who asks for a signature and, mindful of the shuffling line, gives a hurried testimony: after having trouble getting pregnant, she renounced palm reading . . . then conceived two months later! Locke gives a knowing nod. “That’s a really big deal.”

As night falls on Global Vision, Locke addresses the crowd. “People are ready, there is no doubt,” he says. (Yes, amen.) “We’ve been holding off as long as we can. We’re going to see people free tonight.” (Hallelujah, please.) The mood is antsy. No one came here, really, for the açai bowls or theology lessons. We want that down and dirty demon stuff.

The pastor Alexander Pagani takes the stage and works the crowd. Pagani says that among the sea of attendees are demonologists-to-be and slayers-in-waiting who might one day stand on stages such as this. “When you’re casting out demons,” he says, “you should smile for the camera.” He pits different sections of the tent against one another, drumming up action. “Let me talk to this side, they’re too religiooousss over here,” he says, letting the word vibrate in the air like a schoolyard taunt. No one wants to be trapped in that moribund milquetoast normie Christianity. “What about over here, you’re not religiooousss? What about back there?”

The crowd is on its feet now, pumping fists and waving flags. Pagani instructs us to raise our hands and prepare for a spiritual outpouring. “Come on, come on—cameras, catch this all over the building,” he says, pointing. Arms lift to the stage, swaying like a sea of fleshy antennae. We are all deputized, at this very moment, to act as junior Demon Slayers in the battle that is about to commence.

Locke takes the stage, nodding approvingly. “The man of God has primed the pump for us,” he says. “We’re ready, we’re ready.”

The music drops out. Locke asks the crowd to repeat after him in unison. “I renounce you, Satan . . . and all of your demons,” he begins, pausing after each phrase for the response. “I declare before God . . . that you are my enemy . . . I will submit to God . . . I close the door in my life . . . to all occult practices . . . ” Locke’s shirt glistens, and he wipes sweat off his face with a rag.

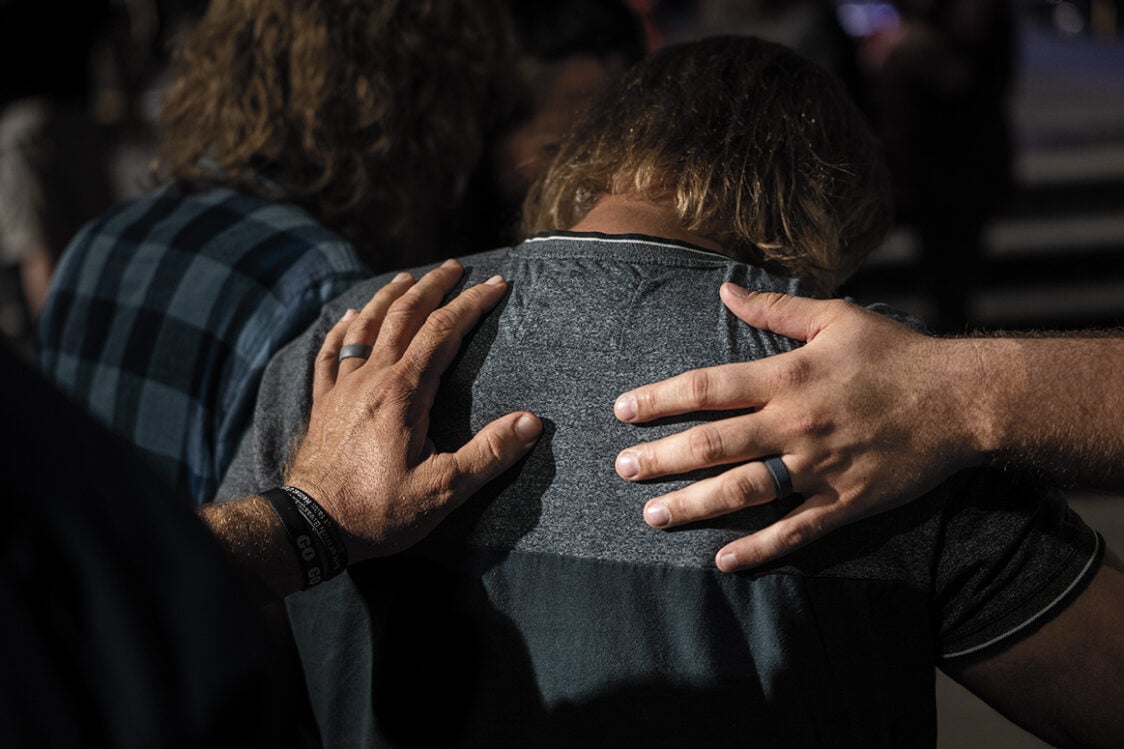

Slowly and then with gathering speed, hundreds of exorcisms erupt. In the tent, in the overflow space outside, everywhere, men and women begin falling to the ground.

Locke continues: “I come against every evil spirit that hinders my walk with Jesus. . . . Come out right now, in Jesus’ name, come out, come out . . . ”

A woman has collapsed in the gravel, writhing in the dust, as two volunteers honk and blast on shofroth pointed at her head. A third helper grips the air near her mouth, pantomiming as if he is wrestling and strangling an unseen monster to the ground.

Every spirit of tarot cards, come out, palm reading, come out . . .

A young man is tending to a dribbling nosebleed with a washcloth—a sign, he says, that he has just been freed from a spirit of video games. “Was it that Slender Man game?” his friend asks. “Maybe,” he responds. “That was super demonic.”

I claim deliverance from any and all evil spirits’ strongholds, generational curses which may be in me or operating around me . . .

I push through the crowd, a lanyard dangling from my neck, surrounded by the sounds of deliverance: squeaks, squeals, a stray bark. A hand extends into the aisle, gripping my shoulder. I pass them an airplane barf bag. Someone begins retching.

Clairvoyance, come out, channeling, come out, come out, horoscope demons, out right now, out every demon of astrology, come out right now . . .

When you are at the pounding center of a mass deliverance, the scene can feel shambolic, but there is an order to things, perceptible in real time. If someone begins twitching and moaning, looking like they’re about to go under, the best practice is to clear some space so that they may crumple to the ground without injury. Don’t barge in, but if you find yourself among those assisting the demon-tormented, the rule of thumb, like in any good collaborative improv, is an attitude of “yes, and . . . ” Be supportive. Don’t hog the exorcism. Be patient but firm. Tools, like special anointing oil or shofroth or prayer flags, are good and welcome, but not necessary.

At the edge of the tent, a rosy-faced lady is surrounded by a band of six helpers. “My sister was a witch when I was growing up,” the lady says, then scrunches her face and howls in a dark, feral voice. One helper grips her chin and speaks now to the demon within. “Enough of this,” they say, clapping hands like a scolding schoolteacher. “Come all the way out!” The lady’s voice turns meek now. “I forgive myself for not taking care of myself,” she whispers, cowed and apologetic, “for thinking that sex is love.”

Exorcisms may drag on for an hour, or several. Locke says his record is eighteen. Others last only a few minutes. I see a girl, no older than twelve, kick and howl through deliverance, only to bounce back to her feet moments later, playfully chasing her friends outside. After her exorcism, the rosy lady unpacks a Tupperware of snacks, slowly peels a banana, and munches away quietly.

Caparas was on a dogged hunt for what he called the powfactor, capturing on film the knockout scenes that pack a punch. They can’t seem contrived or staged. The kind of ready-made shot that looks like it was already edited for film. Crutches thrown aside . . . Pow. A tearful testimony . . . Pow. The ecstatic redemption of deliverance . . . Pow.

The volunteer crew has been tasked with spotting subjects for follow-up interviews. The group chat fills with pictures, contact info, and brief memos:

He had worked for a pornographer; was delivered from many demons

Set free from Lilith soul ties

Spirit spouses

Rejection

Unworthiness

Abandonment

His wife, Emily, was delivered from Lilith, 5 spirit spouses, and a stronghold of rejection

Caparas and Lamberg gather outside to film one such testimony, that of a man who says he was freed from demons and healed of a near-fatal brain tumor. Caparas prompts a bit while Lamberg focuses through a viewfinder. The healed man is shy at first but then warms to the role, going on for a half hour. Lamberg shakes off an arm cramp. Did it have the pow factor? “Good stuff,” he says. “Maybe a little long.”

Criticisms of the Demon Slayers generally fall into discrete camps. One rests on a theological technicality and is generally heard from the Protestant, non-Pentecostal crowd: true believers in Jesus, the argument goes, simply cannot be possessed by demons, as they have already given their souls to Christ. The Slayers are heretical. Another comes from the skeptical debunkers: anyone promising supernatural wonders is a crude scamster, this one goes, selling false hopes to the down-and-out who ought to be going to a therapist or hospital instead. The Slayers are harmful grifters. Undergirding both objections is another: Isn’t there just too much of the Jim and Tammy and Weekly World News in it all? The Slayers are tasteless. Yet it is here, in the pageantry, that the Slayers are at their most compelling.

It is a familiar refrain, heard at journalism conferences and industry roundtables on the subject, that the Media, with its thickheaded secular arrogance, has failed to understand the enduring force of the Religious. It is a self-flagellation and incantation: The media doesn’t get religion. The Religious is the sui generis otherworldly; the Media is the epitome of the profane this-worldly. The reporter tasked with interpreting the Religious, a version of this mantra follows, must be especially mindful and sensitive in order to do an adequate job of covering the faithful. This is at once a scold and flattery, resting on the idea that such subjects need and require special reportorial translation. Yet here, among the career revivalists with their movie franchises, it is a distant notion, harder and harder to hold on to. These are not lonesome characters, silent and unheard without my pen, but those who understand well that religion is at once banal and spectacular, a thing given life through showmanship.

Church employees check on me occasionally throughout the weekend, saying, Have you ever seen anything like this?, and Caparas asks if they might get me to sit for an on-camera interview before the weekend is out. Someone pats my back: “You could make the cut!” As my reporter’s notebook fills and Locke Media cameras roll, I am left to wonder just how different, in the fullness of time, our creations will be from each other.

Locke preaching at a Sunday-evening deliverance service at Global Vision Bible Church

Onstage, the Demon Slayers pit themselves against a limp and sissified American church, deriding mainstream houses of worship as anemic Christian-in-name-alone places of fussy theological debates and snoozy Sunday worship, defeated and decayed, moldy and morose. In contrast, this here is an exhilarating, slap-you-in-the-face, roaringly Spirit-led, experiential thing, animated by that gutsy supernaturalism that has been forgotten for all too long. The miracles: Cancers evaporate. A woman is helped out of her wheelchair and takes several halting steps forward. Pow, pow! Yet the ills these Slayers diagnose and the demons they battle can also feel more modest and familiar, coming less from a distant Apostolic Age than from our present Therapeutic Age. Among more far-flung enemies are the spirits of codependency, ADHD, OCD, IBS, dyslexia, narcissism, procrastination, lactose intolerance. At one point, Locke roars, “Tell that gluten-free demon, Up and out, right now!”

There are breaks from the demon-slaying for feel-good worship. The band reappears between acts. A mosh pit forms in a small clearing. Someone is doing rave hands as bouncing teenagers lock arms and dizzy themselves in tight circles. One man waves his cowboy hat above his head like he’s at a rodeo. A small boy does a limb-twisting Fortnite move as the crowd urges him on. Women kick off their shoes and unfurl gauzy prayer flags, which they twirl in trippy figure eights.

The pastor Mike Signorelli now delivers an abridged version of his path into demonology. He runs in little circles, overcome by the power of his testimony, and breaks into tongues. Signorelli is at work on his own movie, a Demon Slayer spin-off, and takes a moment to screen a preview. “We’re going to basically do our version of the Marvel Universe, redeemed,” he says into the mic. “How many believe that we just need to keep putting out movies?”

The answer is an exultant Yes! but this gets at a question that the team has been wrestling with all weekend: How long can the show go on? They share anxieties with me: audiences are capricious, appetites shift. Backstage, I join brainstorming sessions. No one wants Come Out in Jesus Name 2 to be a boring retread of the first film. There could be a new theme of prophecy, someone offers. A leitmotif about the pitfalls of celebrity. I contribute: “Sort of like a golden-calf thing?” There are nods. “Yeah, yeah.” Another wonders about a more historical angle, reaching back into antiquity to explore the history of demons, almost like an Ancient Aliens–style prequel. “A sequel is just typically not as good as the first movie,” the co-director Romero says.

Other forces threaten the franchise. Some grumble about stage routines getting lifted without credit. “I don’t have a copyright on revival, but . . . ” one Slayer complains backstage, trailing off. “That’s plagiarism!” Feuds, now and again, break out between the stars. One might publicly accuse another of being animated not by the Spirit (uppercase, good) but by spirits (lowercase, bad). Adams, the former cage fighter, got into a spat with Weaver days before the event. Locke explained the unseemly brouhaha to Caparas off-camera. Caparas gasped. “He used the Jezebel word on her?” Adams denies the charge but, prudently, steers clear of the conference.

Evening descends on the third day, and we gear up for the final blitz. People hurl crutches and menthol cigarettes and vapes and miscellaneous drug paraphernalia onto the stage, the items doing dreamy arcs in the air before clattering at the feet of pastors who then hoist them up, like trophies, as empirical evidence of addictions and ailments banished. Caparas moves from side to side with his camera, beaming. Then the house lights come on, screens flashing with service times and QR codes. Bored children tug on their parents’ sleeves to go. The exorcists exit the stage, change out of their sweat-drenched clothing, and retire to the hospitality room, where someone has delivered steaming trays of taco fixings.

Cameras are stowed away, and the tent quiets. But some linger. I see a straggling exorcism and am motioned to join. We four are gathered together in a circle, at the center of which is a young man, head bowed. He rocks slowly, as if he were an infant, while someone whispers in his ear, and I step in to lay my right hand on his bare shoulder, which feels clammy and feverish to the touch. We wait silently, expectantly, until he moans, the tears finally springing from his eyes . . . Pow.

A breeze blows as we exit. A scarecrow leans crookedly in a neighboring field, and a huge bird of prey, flapping shapeless wings, lifts off the side of the road. The moon glows above us, orange as the soft insides of a ripe melon.