Meloni preferisce Rocca a Rampelli nel Lazio: rottamata la corrente di Colle Oppio

16 Gennaio 2023

There Is a Light That Never Goes Out

16 Gennaio 2023The philosopher, who died this month, defied stereotypes by remaining true to his moral sensibility.

Mr. George is a legal scholar and political philosopher.

Sir Roger Scruton, who died this month at age 75, was a longstanding and dear friend of mine. Although we represented different philosophical schools — Roger leaning in a Kantian direction, I being a dyed-in-the-wool Aristotelian — our interests and ultimate conclusions often overlapped. I learned an enormous amount from reading his work and even more from our conversations.

Roger was widely known as a “conservative philosopher”— indeed, the most important Anglo-American conservative thinker of his generation. It’s true that he was a conservative; it’s also true that he was a philosopher. Many of his philosophical views can truthfully be labeled “conservative.” But to honor the truth in full, it is necessary to explain, with respect to any particular view Roger held, the sense in which it was conservative. To do so will show the important ways in which Roger defied stereotypes.

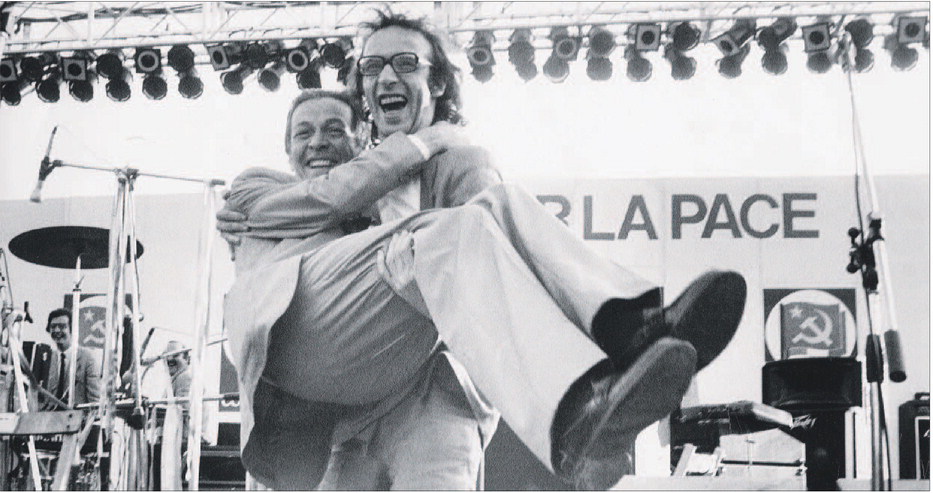

Like conservatives of all descriptions, Roger loathed and opposed Communism, which he regarded as a soul-destroying abomination (and not just as a failed promise of economic prosperity), and all forms of socialism. So he found little to like in the Labour Party of his native Britain, even in the Tony Blair era, or in the Democratic Party in the United States, even before its leftward lurch in the 21st century.

Yet Roger was far from fully on board with the economic philosophy of the British Tories or the American Republicans (or the mainstream of the Anglo-American conservative movement).

First, he believed that the free-market enthusiasm of Margaret Thatcher and Milton Friedman made economic policy too central, relying on it too much to solve social problems and shape society. In this respect, he thought, it shared an error with its great foe, Marxism.

Second, though Roger believed in market mechanisms and fervently opposed central planning and what he saw as a dependency-inducing welfare state, he denied that the outcomes of free exchanges are automatically just. Liberty, while important, was for him only one important value among others like community and solidarity, order and decency, honor and faith.

And so he thought a variety of regulations may be needed, and therefore justified, to protect persons and valuable institutions of civil society — what Edmund Burke (and Roger was nothing if not a Burkean) called “the little platoons” that should play the lead role in promoting health, education and welfare, and in forming new generations in the virtues people need to thrive and contribute to society. Here, Roger joined the iconic American neoconservative Irving Kristol in giving capitalism only “two cheers” — perhaps no more than one and three-quarters.

Roger was willing at times to ally himself with classical liberals, and even Austrian-school libertarians in the struggle against Communism, bravely leading seminars and building underground institutions in Soviet-dominated Eastern Europe. But that should not obscure a profound intellectual-moral difference: Roger rejected “individualism” in any serious sense. Nothing was more fundamental to his moral and political thought than the dignity of the human person; but he understood that to flourish, persons need relationships, beginning with the family.

Central to Roger’s disagreement with his more libertarian allies was his belief in unchosen (and in that sense “natural”) obligations — duties we have simply by virtue of being human and born into a certain family, community, or nation. We do not come into the world as bare individuals who can develop an identity entirely from scratch.

Indeed, Roger was the leading philosophical defender of love of home and one’s own, what he called “oikophilia.” Of course, as a humanist and Christian he recognized duties to all of humanity — even duties of love (understood as being less about feeling than about willing): All are brothers and sisters under the fatherhood of God, who made us all in his own image. But Roger also held that one naturally and rightly has a special love for, and duties toward, members of one’s family, tradition of faith, local community and region, and fellow citizens.

Roger’s oikophilia, and his rejection of “multiculturalism” (which he considered anti-cultural in that it melted the different cultures into a monoculture of contemporary upscale progressive ideology), provoked ignorant and excitable people to accuse him of xenophobia and racism. In fact, Roger respected other cultures a great deal more than most progressives of my acquaintance do. He learned Arabic in order to read the Quran, and he admired the tradition-transcending contributions of the great medieval Islamic philosophers. He made careful, in-depth studies of Hindu and other Eastern traditions of faith precisely in search of the wisdom he regarded them as possessing.

Roger often explained his conservatism with a sound bite, which, naturally, oversimplified matters. He told the story of watching protesters in the streets from the window of his apartment in Paris in May 1968, and realizing that building things of value (communities, societies, nations, legal and economic systems, institutions of civil society) is hard and takes time, while destroying them is easy and often accomplished in a flash. It was then, he said, that he became, or realized that he was, a conservative.

Moreover, he recognized that the most important things people build, even more important than the cathedrals and great works of art and music he so loved, are not primarily the result of planning. They develop organically over time, with trial and error, as the work of many hands (an example is the common law of England). Recognizing this, conservatives should, he argued, seek to protect these things against those who would tear them down out of a misguided zeal for what they saw as the demands of liberty, equality, social justice or even the free market.

The conservative can cheer moderate reforms (organic things do grow and therefore change), but the conservative’s fundamental goal is to conserve. That spirit, by the way, made Roger an ardent, but old-fashioned and therefore moderate, conservationist — a kind of Green Tory who believed responsible stewardship of the natural order crucial. He thought that good stewardship begins with regard for the local landscape and architecture.

Left-wing philosophers — heirs, in a sense, to 1789 — believe that philosophy’s point is to chart how the world should be remade. In Marx’s words, “The philosophers have thus far merely interpreted the world; the point is to change it.” As if to play the role of Marx’s straight men for one of his pithiest lines, some conservative philosophers have sought to explain that the social world is as it is (or was what it was until the left somehow changed it) because it had to be that way and cannot be substantially changed.

Roger was a different kind of conservative philosopher. True, he did not think philosophy, or anything else, could usefully plan or radically reform the world. He was not a Marxist even in that limited sense. There was none of the spirit of 1789, or 1968, in him. But he believed that philosophy can help us see the value of good, if imperfect, things — communities, institutions — that have grown up organically, and that it can show us why we should fight to preserve them and how we can make our own contribution to their development, sometimes even by way of moderate reforms.

Robert P. George is a professor of jurisprudence at Princeton University.

Now in print: “Modern Ethics in 77 Arguments,” and “The Stone Reader: Modern Philosophy in 133 Arguments,” with essays from the series, edited by Peter Catapano and Simon Critchley, published by Liveright Books.

The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips. And here’s our email: letters@nytimes.com.

Follow The New York Times Opinion section on Facebook, Twitter (@NYTopinion) and Instagram.