Strategie di Piccini «Scelta politica chiara basta spopolamento»

20 Febbraio 2026

Andrew arrestato, Trump minaccia, la monarchia vacilla: il mondo nell’ora delle crepe

20 Febbraio 2026Parte seconda: Piancastagnaio. Il presidio si consolida, l’orizzonte si allarga. Part Two: Piancastagnaio. The Garrison Consolidates, the Horizon Expands

A metà del secolo la logica cambia. Non si tratta più di impiantare strutture, ma di aggiornare quelle esistenti. Dal 1450 in avanti compaiono “libri delle bombarde” e mandati che riguardano anche Piancastagnaio: segno che il presidio pianese ragiona già in termini di artiglieria, non più soltanto di difesa passiva. La polvere da sparo ha cambiato le regole del gioco, e chi presidia una rocca sul confine lo sa.

Nel 1465 il Consiglio Generale della Repubblica delibera l’innalzamento della Rocca e la costruzione di una nuova cerchia di mura a difesa del borgo. È un intervento politico prima ancora che edilizio: Siena investe nella montagna, la considera degna di un aggiornamento all’altezza dei tempi. Il cantiere che ne segue, tra il 1471 e il 1478, è il più importante dell’intero Quattrocento pianese. Le date sono impresse nelle pietre: “1471–1478” si legge ancora oggi sulla scarpata a nord del mastio. La struttura viene potenziata con una copertura inferiore a scarpa per resistere all’impatto dei proiettili, le vecchie mura vengono rinforzate da contrafforti, sul maschio viene aggiunta una corona di mensole e archetti pensili. Non è restauro: è rifondazione. Qualcuno ha voluto che quella data restasse lì, incisa nella roccia, come a dire: da qui in poi siamo un’altra cosa.

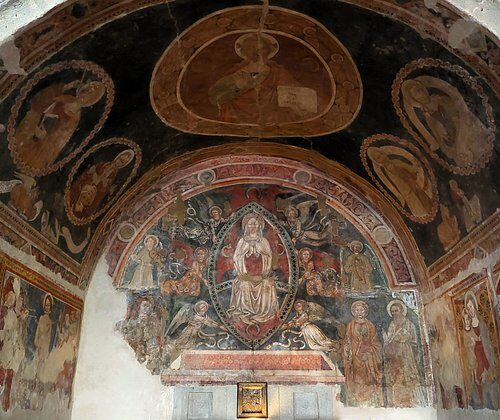

Sul piano artistico, la metà del secolo porta un indizio di tipo diverso. Nel 1468 un maestro pittore orvietano, Giovanni di Pietro, viene pagato per dipingere nella chiesa di Santa Maria delle Grazie. Non è solo un fatto devozionale. È la prova che Piancastagnaio non è una periferia chiusa su se stessa, ma una cerniera attiva tra Siena, Orvieto e Viterbo. Le maestranze si muovono, le iconografie circolano, le committenze parlano lingue diverse. Un pittore orvietano che lavora in un borgo amiatinosenese, nello stesso decennio in cui il grande ciclo del Pellegrinaio del Santa Maria della Scala viene completato a Siena, dice che i confini politici del Quattrocento sono meno impermeabili di quanto sembri sulle carte geografiche. Gli artisti passano, portano forme e modelli, e qualcuno a Piancastagnaio li chiama, li paga, li aspetta.

Anche la pieve di Santa Maria Assunta conserva elementi quattrocenteschi negli arredi e nelle strutture liturgiche, a conferma di una stagione di aggiornamento che non riguarda solo il presidio militare ma l’intero tessuto devozionale della comunità pianese.

Resta da chiarire il legame con il Santa Maria della Scala. Il grande ospedale senese gestiva nel Quattrocento un sistema di grance e ospedali periferici che copriva vaste aree dello Stato, dalla Val d’Orcia alla Maremma. Se la documentazione archivistica dello Spedale attestasse una dipendenza formale dell’ospedale locale da quello senese, la comunità pianese si collocherebbe dentro una rete assistenziale sovralocale di primo ordine. Il Crocifisso conservato in loco è un segno tangibile di quella storia. Le serie documentarie dell’Archivio di Stato senese potrebbero restituirne la trama completa. È uno di quei fili che vale la pena tirare.

Se si guarda l’insieme, la sequenza è coerente: tra il 1345 e il 1430 Siena conquista e radica il controllo; nel 1416 lo Statuto e i primi lavori alla Rocca; negli anni Venti il castellano e il presidio; nel 1424 il convento; nel 1465 la delibera di ampliamento; nel 1468 la committenza pittorica orvietana; tra il 1471 e il 1478 il cantiere che dà alla Rocca la forma che ha ancora oggi. Non sono episodi casuali. Sono gli effetti di una stabilizzazione politica che trasforma un confine in un nodo amministrato, una fortezza contesa in un punto di scambio, un aggregato di case arroccate su uno sperone di roccia in una comunità che ha imparato a riconoscersi.

E qui, lo ammetto, ci sono cascato anch’io. Mettendo insieme date, atti, cantieri, maestri, ho visto emergere una trama che prima non era evidente. Non un elenco di fatti, ma un movimento. Piancastagnaio che nel Quattrocento passa da terra contesa a comunità strutturata, da fortilizio isolato a punto di scambio tra territori, da nome su una mappa di confine a luogo dove si costruisce, si prega, si commissiona, si vive. A volte basta allineare i documenti perché un secolo intero smetta di essere una somma di note a margine e diventi una storia. E quella storia, in questo caso, è ancora qui: incisa nella pietra del mastio, dipinta sulle pareti del chiostro, scritta nei primi capitoli dello Statuto pianese. Una lettura attenta aiuta a coglierne il senso.

Part Two: Piancastagnaio. The Garrison Consolidates, the Horizon Expands

By mid-century the logic changes. It is no longer a matter of establishing new structures, but of updating existing ones. From 1450 onward, “books of bombards” and mandates also concerning Piancastagnaio begin to appear: a sign that the Pianese garrison is already thinking in terms of artillery, no longer merely passive defense. Gunpowder has changed the rules of the game, and those who guard a fortress on the frontier know it.

In 1465 the General Council of the Republic resolves to raise the Rocca and to build a new ring of walls to defend the village. It is a political intervention before it is an architectural one: Siena invests in the mountain, considering it worthy of an upgrade suited to the times. The construction site that follows, between 1471 and 1478, is the most significant of the entire fifteenth century in Piancastagnaio. The dates are carved into the stone: “1471–1478” can still be read today on the slope north of the keep. The structure is strengthened with a lower sloping scarp to withstand the impact of projectiles; the old walls are reinforced with buttresses; a crown of corbels and hanging arches is added to the main tower. This is not restoration: it is refoundation. Someone wanted that date to remain there, carved into the rock, as if to say: from this point on, we are something else.

On the artistic level, mid-century brings a different kind of sign. In 1468 an Orvietan master painter, Giovanni di Pietro, is paid to paint in the church of Santa Maria delle Grazie. It is not merely a devotional episode. It proves that Piancastagnaio is not a closed periphery, but an active hinge between Siena, Orvieto, and Viterbo. Craftsmen move, iconographies circulate, patrons speak different languages. An Orvietan painter working in an Amiata-Sienese village, in the very decade when the great Pellegrinaio cycle at Santa Maria della Scala is completed in Siena, tells us that the political borders of the fifteenth century were less impermeable than they appear on maps. Artists travel, bringing forms and models with them, and someone in Piancastagnaio calls them, pays them, waits for them.

The parish church of Santa Maria Assunta also preserves fifteenth-century elements in its furnishings and liturgical structures, confirming a season of renewal that concerns not only the military garrison but the entire devotional fabric of the Pianese community.

The link with Santa Maria della Scala remains to be clarified. In the fifteenth century the great Sienese hospital managed a network of granges and peripheral hospitals covering vast areas of the State, from the Val d’Orcia to the Maremma. If archival documentation from the Spedale were to attest a formal dependency of the local hospital on the Sienese institution, the Pianese community would be situated within a high-level supra-local welfare network. The Crucifix preserved locally is a tangible sign of that history. The documentary series in the Siena State Archives could restore the full texture of this relationship. It is one of those threads worth pulling.

If we look at the whole, the sequence is coherent: between 1345 and 1430 Siena conquers and consolidates control; in 1416 the Statute and the first works on the Rocca; in the 1420s the castellan and the garrison; in 1424 the convent; in 1465 the resolution for expansion; in 1468 the Orvietan painting commission; between 1471 and 1478 the building campaign that gives the Rocca the form it still has today. These are not random episodes. They are the effects of political stabilization that transforms a border into an administered node, a contested fortress into a point of exchange, a cluster of houses perched on a rocky spur into a community that has learned to recognize itself.

And here, I admit, I fell into it as well. Putting together dates, acts, construction sites, masters, I saw a pattern emerge that had not been evident before. Not a list of facts, but a movement. Piancastagnaio in the fifteenth century moving from contested land to structured community, from isolated stronghold to point of exchange between territories, from a name on a border map to a place where people build, pray, commission, and live. Sometimes it is enough to align the documents for an entire century to cease being a sum of marginal notes and become a story. And that story, in this case, is still here: carved into the stone of the keep, painted on the walls of the cloister, written in the first chapters of the Pianese Statute. A careful reading helps us grasp its meaning.