In September 1904, Sigmund Freud set out with his brother Alexander on their annual Mediterranean holiday. They were aiming for Corfu, but the heat was so intense they took a ship from Trieste to Athens instead. The two men climbed the legendary hill above the city to visit the Acropolis and it was there that Freud became overwhelmed with a strange and bewildering sensation. “By the evidence of my senses I am now standing on the Acropolis,” he later wrote, “but I cannot believe it.”

This was not just the tourist’s usual expression of amazement: here we are at Machu Picchu, Petra, the Pyramids – and it feels so unreal! Freud experienced a complete incredulity that the Acropolis actually existed at all. He had read about it from childhood, studied engravings and daguerreotypes of the Parthenon, so elegant, grave and stoic; but now that he was here the strongest feelings were of filial guilt (that his father never saw it) and powerful disbelief. The experience would baffle him for decades.

This is the subject of a small but enthralling show at 20 Maresfield Gardens, the north London house to which the Freud family fled from Vienna to escape the Nazis in 1938. “Our last address on this planet” is now the Freud Museum. The exhibition centres on the celebrated essay Freud wrote at the age of almost 80, titled A Disturbance of Memory on the Acropolis. This is nothing less than an attempt to analyse himself, and his experience, after 32 years of thinking. It is one of the great explorations of our peculiar inability, sometimes, to rejoice.

The story is told in postcards, letters and documents, in images of all sorts, and in the objects and sculptures Freud himself collected. It opens halfway up the wide staircase with a colossal sepia photograph of the Acropolis at twilight, taken by the Swiss photographer François-Frédéric Boissonnas in 1907, and includes other visions of the Parthenon beneath glowering storm clouds or at eerie dusk.

Freud knew the prints of the Acropolis by German Romantic artists shown here, and was immersed in Ancient Greek culture from a very young age. He studied the language at primary school, kept a diary in Ancient Greek and proposed that his new baby brother be named after Alexander the Great. How dismaying (and potentially comic) that he couldn’t get the Athens carriage driver to understand his directions to the Grand Hotel because they were uttered in Ancient Greek.

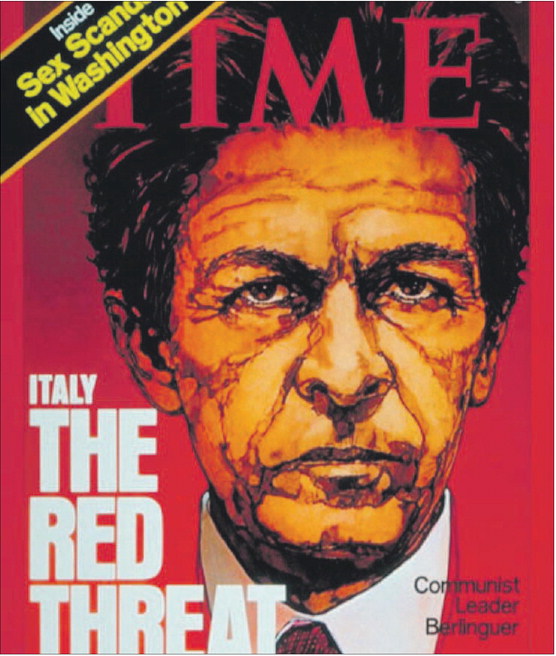

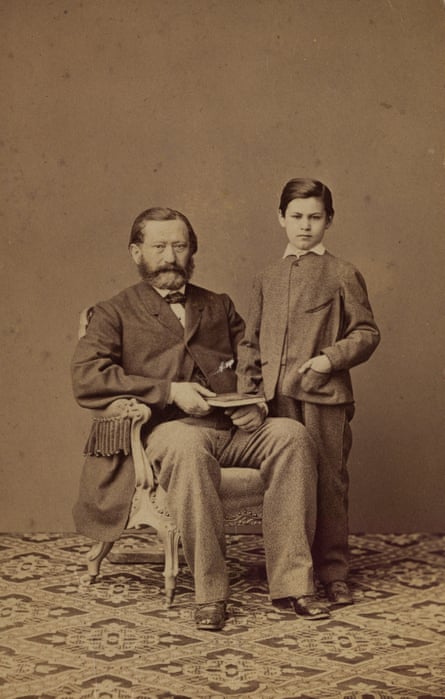

Here’s the hotel, the restaurant the brothers dined in, the ship they took – the Urano, a ghost vessel drifting dark on pale waters – in period photographs and cards. The curator, Marina Maniadaki, grew up in Athens with the Acropolis above her shoulder at all times, and her sense of its hovering presence elevates the whole show. But very early on she includes a studio photograph of Freud around the age of 10 with his father, which will gather new meaning as you go.

The trip to the Acropolis was accidental, pure chance, since the brothers were destined for Corfu. Freud kept seeing the numbers 61 and 62 along the way (prompting thoughts of his own mortality: would he die at this age?). He wore his best shirt to climb the hill. Everything is set for heightened significance.

The appalling disbelief on arrival is compared, in the famous essay, to seeing the body of the Loch Ness monster lying stranded on the bank and realising that what they told him at school turned out to be true after all (if too late). Many serpentine objects appear in cases – bracelets, statues, votives – though of course they may have had quite other meanings to Freud. The day he visited the Parthenon, the museum was, alas, closed, so that he never saw the statues of Athena that haunted him – this goddess, who springs like an idea from Zeus’s head. Here is his ancient bronze statue of Athena, apparently raising one arm to make a point: his favourite possession.

But what Freud realises so late in life is that his response is a form of repudiation that relates in part to his father. “It seemed to me beyond the realms of possibility that I should ‘go such a long way’ further than him.” Jakob Freud was a wool merchant and autodidact. In the photograph, he sits with a book on his lap, like an attribute, while the child Sigmund stands beside him with a sceptical frown: one face open and outward, the other already inward.

Freud’s disbelief at having gone so far is both psychological and geographic. At no point did he imagine travelling as far as Greece, or exceeding his father in so many ways. It is as if he extends his bewilderment about both to doubts about the very existence of the Acropolis itself.

A tiny clay mould appears emblematic of this inner-outer blur. This Ancient Greek head holds a little face inside, in negative. It comes from Freud’s own collection.

Finally, there is the original essay itself, written as a letter to the French writer Romain Rolland. Freud’s late handwriting resembles a tide of recurring ripples, rising bottom left to top right; a surprise in itself, in a show about revelations that keep on coming to mind. It has taken Freud more than 30 years to think it through, and his last realisations are startling and indivisible from the entirety of his long existence. Three years later, he will die of jaw cancer in the house where this letter now lies. His ashes will be sealed, at Golders Green, in a Grecian urn.

-

Tracing Freud on the Acropolis is at the Freud Museum, London, until 7 January 2024